REPORTER'S NOTEBOOK

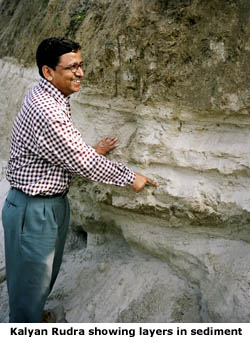

Dr Kalyan Rudra, a geography

professor in Kolkata, has asked us to stop and meet him at a  village called

Panchanandapur in Maldah District in West Bengal. He wants to show us Farakka

and its consequences firsthand.

village called

Panchanandapur in Maldah District in West Bengal. He wants to show us Farakka

and its consequences firsthand.

We set sail from Rajmahal on the southern bank

of Ganga. In the middle of the river lie huge islands where dacoits are rumoured

to hang out, all the better to catch unsuspecting prey like us, then scoot

back to the safety of their islands. On the far bank lies West Bengal, the

same country but in many ways a different world.

Rajmahal is at the northeastern-most tip of

the vast Deccan Plateau. It's granite and basalt, so the river can't cut into

it. Not coincidentally, between Sahibganj and Rajmahal the southern bank is

full of quarries and stone crushers, building materials destined for West

Bengal. The river therefore has to run along in a straight line eastwards

until it finds an opening and plunges south towards the Bay of Bengal.

As we row across Ganga from

Rajmahal to West Bengal, both Graham and I simultaneously have the same thought:

we're heading into delta country. The vegetation is no longer the same. On

the West Bengal side are thick forests of palm trees, muezzins sound the call

to prayer, tractors race up and down, small fishing boats dart in and out

of the shore, everywhere there are large electricity pylons. The countryside

literally hums with activity. Graham and I instinctively feel at home here.

This is a place we're familiar with from past journeys.

Tivari and Martine have crossed ahead by ferry

in the Scorpio to find our contact in Panchanandapur, a young activist called

Torikul Islam. Torikul heads an organisation - Ganga Bhangan Protirodh Action

Nagarik Committee - that helps rehabilitate villagers in Maldah District displaced

by the annual floods.

Panchanandapur comes into view. At

the top of the very steep river bank a huge crowd awaits us on a wide stone

embankment. We clamber up: on the other side lies another river, effectively

separated from Ganga by this embankment of earth and huge boulders. After

the traditional garlands and speeches, the village welcoming committee asks

us the usual questions, why we are travelling down Ganga, etc. Kalyan Rudra

takes us inside a thatched bamboo hut while the others go to set up the tents

in the garden of Jalaluddin Ahmed, the village patriarch.

Kalyan Rudra is not the sort

of man who’d stand out in a crowd. He's the complete opposite of RK

Sinha; small in size, voice, and ego. RK Sinha didn'tt even realize he was

a fellow professor when he first met him and treats him as someone of no particular

consequence. However, Kalyan Rudra has a highly original mind and is accepted

by these villagers, even though everything about him says city man. For some

reason he's here in a relatively nondescript college in northern Kolkata,

but the quality of the man and his work are extraordinary.

Kalyan rolls out a map, explaining Ganga's drastic

shifts these past thirty years. The river has traditionally oscillated back

and forth within clearly-defined boundaries. But now there is evidence Farakka

has accentuated this shift. The crowd press against every crack of the bamboo

walls, trying to peer in and get a glimpse. Kalyan then explains the role

of Torikul's organisation. More than eight hundred thousand people have lost

their homes in Maldah District to Ganga in the past ten years: some have moved

across to new sandbanks or chars on the south side of Ganga, back towards

Jharkhand.

His colleague Monatosh Shah takes me on a short

tour of the village to explain Ganga's effects on its land. Monatosh was born

here but now lives in Kolkata and has accompanied Kalyan on the overnight

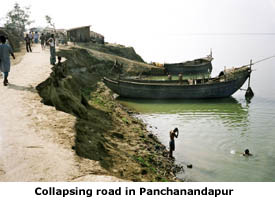

train to Maldah expressly to meet us. Monatosh says this embankment is brand

new. It was rebuilt last year after Ganga destroyed the old one. I'm shown

some slides taken the previous year by Mehedi Hasan, a geography teacher in

Maldah City, twenty kilometres away. I don't recognize any of the places -

the embankment the slide shows is now a hundred metres out into the river!

Mehedi puts up another slide:

a two-story brick building surrounded by forest. He says the building was

called Ganga Bhavan. It housed the offices of the West Bengal Irrigation Department.

It also used to be right here on the river bank in Panchanandapur.

" I didn't see it today!" I tell Mehedi.

" You won't for a few more years,"

he tells me. "Maybe in a few years it'll reappear." The school and

police station have also disappeared in the last year. I am filled with shock

and disbelief. ‘You mean this river moves two hundred metres a year?

‘Sometimes more, sometimes less. Everything

has become distorted because of Farakka. Thirty years ago Panchanandapur was

eight kilometres inland. By next year it may have entirely vanished into the

river. My father's house will be no more!’

Before we turn in - it’s been a long hot

row - Ruhul Islam, a local musician, sings us some Vaviyas, traditional Bengali

folk songs. The bittersweet lyrics are all about how Ganga takes away people’s

land and houses. Some Vaviyas deal specifically with the devastation in Panchanandapur.

Floods, erosion and loss are central to these people’s lives. In one

song, Ruhul Islam lists everything he’s personally lost to the floods,

beginning with his boat. Out of eight hundred thousand people who have lost

their land in Maldah District to erosion and floods, two hundred thousand

of them have emigrated from the district entirely, presumably permanently

to points south.

After dinner in Panchanandapur,

I sit with Jalaluddin Ahmed, the bedridden patriarch of the house whose garden

has become our temporary camping ground.

‘I remember how forty years ago this village

was a prosperous port,’ he tells me. We traded a lot with Rajmahal.

There used to be an indigo factory. The British built it. We had extensive

mango and bamboo groves. Then the erosion began in 1969. Within a few years

it was all gone. I lost everything. Nothing I could do about it. Everything

just disappeared in front of my eyes.’ The indigo factory from British

times has long since been washed away. Jalaluddin personally has already lost

seventeen acres of land.

The next morning at the chai stall I sit and

talk to as many villagers as have stories to tell, most Muslims. Jalaluddin

Ahmed appears fortunate: he still lives in the same house he grew up in.

Chittaranjan Sarkar says,

‘I’ve lost my house six times! Some of us are now actually seeing

old fields reappear on the other side where the river has shifted. I saw my

own farmland reappear over there,’ he points to the chars on the far

bank of Ganga. ‘But West Bengal refuses to grant me - or anyone else

here - legal title. Why?’ He promptly answers his own question: ‘I’ll

tell you why. It’s because the CPM (the Communist party that has ruled

West Bengal since the 1970s) doesn’t want to give our sitting MP a few

hundred thousand new voters. He represents Congress and he’s a Muslim.

So they prefer to keep us stateless!’

Chittaranjan Sarkar says,

‘I’ve lost my house six times! Some of us are now actually seeing

old fields reappear on the other side where the river has shifted. I saw my

own farmland reappear over there,’ he points to the chars on the far

bank of Ganga. ‘But West Bengal refuses to grant me - or anyone else

here - legal title. Why?’ He promptly answers his own question: ‘I’ll

tell you why. It’s because the CPM (the Communist party that has ruled

West Bengal since the 1970s) doesn’t want to give our sitting MP a few

hundred thousand new voters. He represents Congress and he’s a Muslim.

So they prefer to keep us stateless!’

Khider Bux was born in old Panchanandapur village

in 1973. Old Panchanandapur was back then eight kilometres further west, towards

Jharkhand. It’s only now slowly re-emerging from Ganga. He’s especially

bitter that the West Bengal government has never offered him compensation

while it spends crores of rupees dumping heavy rocks along the embankment.

But heavy rocks don’t protect them. The weight of the boulders is more

than the coarse sediment at the base of the river bank can hold. It merely

accelerates erosion.

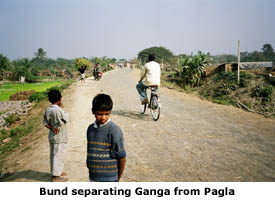

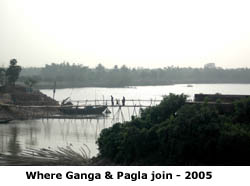

Ganga once flowed into three small rivers on its northern bank - the Pagla,

Chotti Bhagirathi and Kalandri - which used to be old distributaries of Ganga

in past centuries. Now they are each cut off from Ganga by huge stone and

earth embankments, like streets in West Berlin that would suddenly be brought

to an abrupt dead-end by the Berlin Wall, healthy limbs amputated for no apparent

reason. What were the authorities afraid of? PK Parua, the former Chief Engineer

at Farakka, later told me in Kolkata that it was the villagers who had insisted

the West Bengal apply these vast tourniquets. If they did they soon realized

the error of their ways. The natural flood plain of Ganga had been disrupted.

So Ganga did what all rivers do: it tried to break through the embankments

and follow its old course. The results have invariably proved worse than the

original condition.

Saidul Islam still lives here, but he has a

similar identity crisis. Every morning, he takes the ferry to the newly-emerged

char land on the other side of Ganga. He now farms fifty acres there that

he claims were his before they were swallowed up by the river!

Monatosh Shah chips in. ‘The

real tragedy is that people here in Panchanandapur are paying the price of

keeping Kolkata port open. But why should this be at our expense? ‘

Monatosh was born here in 1949 and lost his family house and mango orchards

to Ganga only three months ago. He’s not just angry with the West Bengal

government in Kolkata, he’s mad at New Delhi as well.

Monatosh Shah chips in. ‘The

real tragedy is that people here in Panchanandapur are paying the price of

keeping Kolkata port open. But why should this be at our expense? ‘

Monatosh was born here in 1949 and lost his family house and mango orchards

to Ganga only three months ago. He’s not just angry with the West Bengal

government in Kolkata, he’s mad at New Delhi as well.

‘They never thought of the consequences

of building Farakka. All they could think about was hurting Pakistan. The

barrage doesn’t work anyway. Half its gates are closed because of silting.’

Monatosh tells me, ‘The West Bengal government

has spent two hundred seventy-five crores this year shoring up this thirty-kilometre

stretch of the river. For what? Money thrown into the river. They should have

given it to the villagers. You cannot control the river! You have to learn

to live with the river.’

He lugubriously adds, ‘Otherwise Panchanandapur

may be gone if you come back next year!’

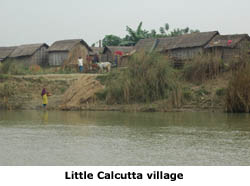

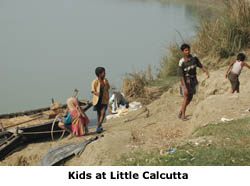

One day Kalyan takes me across

the river to a village called Kashmiuldalla or Little Calcutta, ten kilometres

as the crow flies; three hours by boat in and out of the braided channels

that are Ganga here as it regularly throws up fresh chars. Five thousand former

residents of Panchanandapur have established themselves here on the new char

lands that have reappeared on the southern side of the river. Most of the

chars are just fields, their banks hidden by tall Ganga grass, like new fuzz

on an adolescent’s chin. Then, round a bend, something more substantial

comes into view - large farmhouses, radio antennas, sheep and cows grazing

at the water’s edge. We have arrived at Kashmiuldalla.

Jaffar Ahmed, the village

elder, greets us with a predictable complaint: ‘We want to be West Bengalis

but West Bengal won’t acknowledge us. We have Jharkhand voter registration

cards and they have given us three health centres and ration cards. But we

have to rely on solar power for our electricity. Neither state wants to give

us the connection.’ Jharkhand is simply too far away; the nearest stores

are back in Panchanandapur and Maldah in West Bengal. I still don’t

really understand why West Bengal doesn’t want to have anything to do

with them. The villagers huddle together to confer.

Jaffar Ahmed, the village

elder, greets us with a predictable complaint: ‘We want to be West Bengalis

but West Bengal won’t acknowledge us. We have Jharkhand voter registration

cards and they have given us three health centres and ration cards. But we

have to rely on solar power for our electricity. Neither state wants to give

us the connection.’ Jharkhand is simply too far away; the nearest stores

are back in Panchanandapur and Maldah in West Bengal. I still don’t

really understand why West Bengal doesn’t want to have anything to do

with them. The villagers huddle together to confer.

Finally Jaffar Ahmed decides to tell me what

the villagers believe is the real reason. It’s not just that they’re

Muslim and a potential vote bank for the Congress MP Ghani Khan Choudhary.

It’s a tale of corruption. Relief moneys are given out from Kolkata.

The ruling CPI(M) reasons if they refuse to acknowledge these people even

exist they can skim off money with relative impunity. Obviously, I can’t

prove this. But it’s what the villagers in Kashmiuldalla believe. Who

knows where the truth lies?

Although Mohammed Faqir Ali lost his farmlands

back in 1990, he claims there are definite advantages to living here. The

land is very fertile. Since West Bengal has done virtually nothing for them

- no roads, no electricity, no medical facility, no school, no ration or voting

cards - they’ve built their own mobile tower and solar panels to power

their new homes. ‘And, of course, we don’t pay any taxes!’

And yet, every year, the West Bengal government

spends crores of rupees trying to prevent nature taking its course. It’s

the Indian version of the Anglo-Saxon story where King Canute tries to prove

his dominion over the ocean, seating himself on his throne on the beach and

ordering the tide to stop and retreat. The tide ignores him and his courtiers

rescue him from this gross act of insubordination.

The unspoken fear this day in December 2004

is that Ganga will burst through its embankments and link back up with Pagla,

Chotti Bhagirathi and Kalandri. The three rivers are just waiting to be brought

back to life. These new distributariesof Ganga would then flow naturally into

a bigger river - the Mahananda - which goes far north of Farakka near Gour

before rejoining Ganga just inside Bangladesh. Farakka would effectively be

bypassed.

After a few days of excellent food and company

in the village we set out to row the remaining twenty kilometres to Farakka.

The river has now become awfully broad and flat. The river divides and subdivides

in a maze of broad, flat sandbanks. For the first and only time we actually

lose our way. Which is the main channel? There are no discernible landmarks

and the water itself has changed. It’s become suddenly clear and still,

and here’s a hazy stillness, the feeling of rowing across a vast pond.

But to where and what? Subhash standing at the helm peers into the haze. He

utters just three syllables: ‘ Farakka.’

Seen from upstream the barrage

appears a low faint line in the morning haze, all hints, suggestions and smudges

of colour, Farakka the township is rather lugubrious. On the southern bank

of Ganga, its sole raison d’être nowadays is to regulate the flow

of water through the barrage. Previously, it had housed all the construction

workers and engineers.

It’s a company town built for the sole

purpose of creating the barrage. All neatly laid out, anonymous cream concrete

buildings, living quarters subdivided by letter and number, barbed wire fences,

half a day from Kolkata by train or road. What do wives do to while away the

seasons, I wonder, while their husbands are shuffling papers in these musty

offices? There’s surely a novel to be written here, of petit bourgeois

ambition, intrigue, boredom, and illicit sex.

The sight of Farakka prompts Graham Chapman

to make one last attempt to set me straight. He’s still horrified that

I freely confuse dam and barrage. ‘Look, Julian, a dam stores water.

A barrage is a weir with gates all along for letting water through. This is

the basic difference.’

Graham explains that dams and barrages look

the same. But I beg to disagree. In my imagination, a dam is massive, concrete,

solid, a vast still reservoir stretching far behind the dam at the expense

of people, villages, animals and perfectly good farmland. The massive Tehri

dam in Garhwal is a good example. Lives wrecked, productive farmland flooded

to make a lake thirty-five kilometres long - all to light the lifestyles of

the burgeoning middle-class in Lucknow and Delhi.

But a barrage looks very different. It’s

low-slung, functional, flat. It screams engineering: a huge Meccano set, all

metal and rivets and right angles. I could never fall in love with a barrage.

The river behin d the barrage looks like a normal flowing river, maybe tending

to middle-aged spread as silt piles up; in engineering jargon pondage. A barrage

has gates that can lift and descend to let the river through. Graham’s

correct in his geographer’s precision.

d the barrage looks like a normal flowing river, maybe tending

to middle-aged spread as silt piles up; in engineering jargon pondage. A barrage

has gates that can lift and descend to let the river through. Graham’s

correct in his geographer’s precision.

Farakka Barrage is a defence

installation, which means there are armed guards every twenty metres, and

absolutely no photography allowed. It’s more than two and a half kilometres

long and has one hundred and eight gates Yesterday Monatosh Shah told me half

of them are closed. In daylight it appears even more! It’s built deliberately

across the narrowest point of the river after it’s made its big turn

round the tip of the Rajmahal hills. Important fact number one.

It beggars belief that the

planners never thought about sedimentation. But the construction of Farakka

has always seemed to ignore fundamental hydrological realities. If you effectively

build a wall across a monsoon river, this will obviously upset the hydrological

dynamics of the river upstream. For a start, where would all Ganga’s

sediment go? It can’t all flow through the barrage - there’s too

much of it - so it builds up behind in an erratic pattern.

It beggars belief that the

planners never thought about sedimentation. But the construction of Farakka

has always seemed to ignore fundamental hydrological realities. If you effectively

build a wall across a monsoon river, this will obviously upset the hydrological

dynamics of the river upstream. For a start, where would all Ganga’s

sediment go? It can’t all flow through the barrage - there’s too

much of it - so it builds up behind in an erratic pattern.

Kalyan Rudra says that since Farakka was commissioned

in 1975, the river has dumped so much sand behind the barrage that the riverbed

has risen over seven metres or twenty-three feet. This shallow lake above

Farakka is therefore now no longer muddy, but clear and transparent. Ironically,

Westerners would see this as a sign of good health. But the opposite is the

case: turbidity in India means a healthy river: clear water means no flow.

All because most of the silt has been deposited in front of the barrage at

Farakka.

Ganga historically oscillated within a thirty

kilometre belt every seventy years. Kalyan argues the silt build-up behind

Farakka has ‘made the river unstable.’ This thought never seems

to have occurred to the engineers who designed Farakka.

We eventually get through

and out into the feeder canal, thirty-eight kilometres of concrete-lined canal

straight as an arrow all the way down to Jangipur, where the canal has revived

the virtually-moribund Bhagirathi, and then on to the Hugli, Kolkata and Sagar

Island.

The Bhagirathi bears no family resemblance to Ganga. It appears a charming

pastoral river, civilized, landscaped, the occasional temple to remind me

this is India, not Surrey or Hampshire. As if on cue, the extraordinary palace

at Murshidibad comes into view, a Bengali Hampton Court on the Thames. All

that’s lacking are the swans.

Farakka is basically not working

as envisaged. Forty thousand cusecs of Ganga are diverted down the concrete

feeder canal into Bhagirathi-Hugli, so the port of Kolkata can tick over.

But no big ships come up. Dredging has increased threefold just to maintain

the status quo. The former Chief Engineer of Farakka tolld me back in 2001:

Farakka is basically not working

as envisaged. Forty thousand cusecs of Ganga are diverted down the concrete

feeder canal into Bhagirathi-Hugli, so the port of Kolkata can tick over.

But no big ships come up. Dredging has increased threefold just to maintain

the status quo. The former Chief Engineer of Farakka tolld me back in 2001:

‘We are getting boats up in the port as

large as in 1958!’

I hated to spoil his day. ‘And how large

is that?

‘Oh, eight to ten thousand tons.’

My shipping friends tell me nobody carries anything

today - oil, manufactured goods - in a cargo vessel of less than fifty thousand

tonnes. Tankers and supertankers, of course, are at least twice as big. On

that score whether the volume of water is the same or has increased is largely

irrelevant. Modern ships simply cannot get up to Kolkata from the Bay of Bengal.

They load and unload at Haldia. Kalyan says they’re now thinking of

building a port at the tip of Sagar Island itself.

I’m not sure that’s such a good

idea: the sea at Sagar Island is very shallow for a long, long way out. At

Kolkata, just like every so-called port in the Sundarbans, channels are nowhere

deep enough. There are simply no suitable sites for modern deepwater ports

along the coast of the Bay of Bengal. They’re at best inland ports like

Dhaka and Mongla Port in Bangladesh, suited for the coastal trade.

A whole economic ecosystem has been destroyed

by Farakka. Before Farakka ships regularly brought tea or jute from the north

down the river to be processed in Kolkata’s factories and exported.

In return, finished goods came back up not just to Assam or Patna, but as

far west as Allahabad. All carried up and down Ganga. All this world vanished

for the mirage of keeping Kolkata port open.

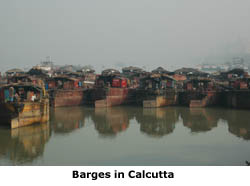

In Kolkata I once rowed out

to some barges moored midstream to talk to the crews. They were mostly Muslims

who’d been working the river since before Farakka. Mohammad Shafiq and

Sheikh Abdul Kalam were taking the Jyoti to Naranganj on the Sittla river,

off the giant Meghna in Bangladesh. The entire journey would take them ten

days.

In Kolkata I once rowed out

to some barges moored midstream to talk to the crews. They were mostly Muslims

who’d been working the river since before Farakka. Mohammad Shafiq and

Sheikh Abdul Kalam were taking the Jyoti to Naranganj on the Sittla river,

off the giant Meghna in Bangladesh. The entire journey would take them ten

days.

‘Yes, it’s fairly slow. A lorry

can do the trip in just ten hours. But then it can only carry ten tonnes.

We can carry a hundred tonnes.’

In the sixties, both men had gone up to Patna

and back, bringing down jute and taking back finished goods. They even remembered

barges coming all the way down from Allahabad.

‘But

since Farakka, that’s become impossible. Business has declined dramatically,

it’s down to just a fifth of what it used to be. Mostly we now take

occasional cargoes of fly ash for building sites in Bangladesh. Otherwise,

we wait here in the Hugli and play cards.’

I asked them as Indians and Muslims if the Ganga was sacred for them too.

‘‘We swim in it because it is pak

(pure).’ Only in theory surely. Ganga at Kolkata appears about as dirty

as at Jajmao in Kanpur. Shafiq sticks to the official line: ‘All rivers

are sacred to Muslims, so we bathe in Ganga. It purifies us before we make

our prayers to God. We don’t worship images and idols. But this river

is made by Allah, so it is pure and sacred to us.’

I asked to be rowed to another barge in mid-channel.

This one had just arrived.

‘What are you bringing up?’ I shout

across.

‘We’re coming from Kidderpore dock,

empty.’ Mohammad Sadiq, one of the boatmen, says they’re going

back down to Sagar Island tomorrow to bring back firewood. Going down empty

one way, not very profitable.

‘There used to be ten thousand barges

here. Now there are just eighty. It’s all because of the decline in

the jute trade, and Farakka.’ I’m sceptical of the figure of ten

thousand barges but not of the decline in the jute trade. The question is:

which is cause and which is effect? Did Farakka accelerate the death of the

jute trade or was it in decline already? In any event, the economic relationships

between upstream and Kolkata are virtually dead today, like so many of the

delta’s rivers.

The failure of the fish ladder

at Farakka has far more serious human consequences. All the fisheries as far

back as Buxor west of Patna have been decimated. The fishermen at Kahalgaon

are right to feel Farakka is the cause of their misery. Coming down Bhagirathi-Hugli,

our skipper Subhash blames Farakka for the plight of the traditional fisherman.

But it’s not only Farakka. He says many fishermen in Bihar have been

driven to leave fishing altogether and have become labourers, rickshaw-wallahs,

even vegetable sellers.

The failure of the fish ladder

at Farakka has far more serious human consequences. All the fisheries as far

back as Buxor west of Patna have been decimated. The fishermen at Kahalgaon

are right to feel Farakka is the cause of their misery. Coming down Bhagirathi-Hugli,

our skipper Subhash blames Farakka for the plight of the traditional fisherman.

But it’s not only Farakka. He says many fishermen in Bihar have been

driven to leave fishing altogether and have become labourers, rickshaw-wallahs,

even vegetable sellers.

His colleague Mahesh says paradoxically, ‘There

are more fishermen than ever!’ How come, if Farakka has cut catches?

‘A kilo of fish now sells for a hundred rupees. That’s one reason

why!’ It used to sell for twenty to twenty-five rupees a kilo. ‘Now

any Tom, Dick or Harry can earn a living because fish prices have increased.’

There are no cooperatives, no loans, no capital for investment. So there are

now at least two distinct fishing communities - the traditional and the johnny-come-latelies.

The latter also use fine-mesh mosquito nets.

‘I think this is why the number of fishermen has increased,’ says

Mahesh. ‘With these ready-made nets anyone can buy them off-the-shelf

and catch their two kg a day. We had to learn to make our own nets. Today’s

youth don’t even know how to tie simple knots.’ Subhash won’t

encourage his own children to become fishermen. ‘They need to get education

to get better jobs. Anyway, the mafia’s gotten involved in fishing.

But if our Mother Ganga dies we will also die. We get everything from her’

Is there any solution?

Our host Jalaluddin Ahmed in Panchanandapur

thinks the only real solution is to break down Farakka, let the river behave

normally again. But the Indian government will never countenance that; it

has too much prestige riding on Farakka. To destroy Farakka would be to admit

they’d been wrong all along. If Ganga can’t flow through Farakka,

will it simply find a way to flow round it - and will Farakka become the ultimate

symbol of India’s, and man’s, hubris?

Nine months later, in September

2005, I get an urgent call from Kalyan Rudra to come back up to Panchanandapur

as soon as possible. Something terrible has happened. Panchanandapur has fallen

into Ganga! I meet Kalyan and Monatosh Shah at Sealdah Station in Kolkata

to take the night train to Maldah.

Nine months later, in September

2005, I get an urgent call from Kalyan Rudra to come back up to Panchanandapur

as soon as possible. Something terrible has happened. Panchanandapur has fallen

into Ganga! I meet Kalyan and Monatosh Shah at Sealdah Station in Kolkata

to take the night train to Maldah.

Torikul Islam meets us next morning, drives

us the twenty kilometres from Maldah towards Panchanandapur. The road is lined

with makeshift tents - villagers forced out of the village inland. In this

flood two thousand houses have been destroyed.

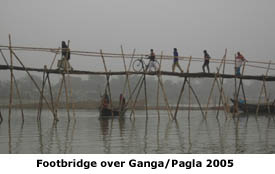

We’re not coming in by the usual road. I soon

discover why. On September 3, 2005, Ganga swept the embankment away and flowed

into Pagla. Most of the village of Panchanandapur collapsed: it now lies deep

beneath Ganga.

The embankment has been almost totally destroyed.

To go to Jalaluddin’s house is now impossible by car. It’s cut

off by Ganga which is now flowing directly into Pagla. The only access to

what remains of the village is by a swaying bamboo footbridge. We cross to

Jalaluddin’s house because he’s invited us to spend the night.

Hardly anything remains of the streets and houses I walked through less than

a year previously. The chai stall, the whole area where we sat, is now buried

deep under a vast new bay of Ganga.

After putting our bags down, we walk back across

the rope bridge to what remains. We sit in the sole remaining dhaba. Monatosh

says: ‘You can see for yourself. Pagla and Ganga have connected.’

The previous winter the West Bengal Irrigation

department had built three kilometres of bed spurs, a form of underwater barrage.

The villagers had assumed they were safe, at least for 2005. I assume this

destruction must have been caused by Ganga flooding but the river wasn’t

in flood - it simply ate away at the foundations of the bank until they finally

collapsed.

Because not a single life was lost, I also assumed

the erosion had taken place during daylight hours. Wrong again. When Tajmal

Huq walked out of his house at two o’clock in the morning on August

24th it had already slipped into the river when he looked back.

The erosion occurred in two phases, on August

24th and then on September 3rd. On the earlier date three hundred and seventy

shops in four neighbourhoods collapsed into the river. But the decisive event

took place on September 3rd. Ganga was already one metre higher than the Pagla.

When the breach occurred, Ganga simply poured into Pagla for several hours

until the levels had equalized. Kedarnath Mundal, a villager I’d met

previously, told me what he remembered.

‘We were sceptical about the erosion work

the previous winter. We even wrote to the President of India. But we never

believed this would happen,’ Kedarnath said. ‘I’ve already

lost my home four times. My existing one is just three hundred metres from

the river, so it looks like I’ll be homeless again this time next year!’

Kedarnath thinks the West Bengal Irrigation

Department should open up the three small rivers - Pagla, Chotti Bhagirathi

and Kalandri - to allow Ganga to flood naturally. ‘If only we had been

given land so we could move before the erosion,’ he laments. ‘No

one died, but we’ve lost all our animals.’ Both schools have collapsed

so his kids are no longer in school.

Over lunch at the dhaba Kalyan explains why and how it happened: ‘Imagine

a river flowing straight into a massive brick wall. What happens? It rebounds

and sets off a current back upstream. The effects of the barrage can be felt

a hundred and ninety-five kilometres back upstream, and you know who has done

these calculations?

But there’s a wrinkle. In the lab, the

current hits the wall at ninety degrees while in real life Ganga hits Farakka

at an angle. The course of the river is no longer a straight line from Rajmahal

to Farakka. Farakka has exaggerated the natural meanders upstream, pushed

the river to one side, so it approaches the barrage at a slant As Kalyan puts

it: ‘The whole hydraulic gradient of the river has been changed.’

And what’s the consequence? ‘This causes a back rush, and the

river seeks an alternative outlet sideways.’

Precisely at its weakest point, at Panchanandapur.

The cause of the collapse of the village therefore wasn’t a storm or

massive flooding. The new hydrological dynamics produced by Farakka had undermined

all the careful efforts of the West Bengal government. The entire embankment

- above ground and below water - had eroded. It was the weight of the boulders

that actually triggered the collapse.

But it was Farakka that was really responsible.

It had forced Ganga sideways, so Ganga then undermined the bank from below.

There’s now nothing to prevent Ganga flowing more and more into Pagla

and then into Mahananda. Now it has united with Pagla the government is worried

it could cut the railway and highway to North Bengal.

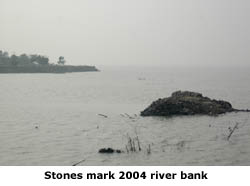

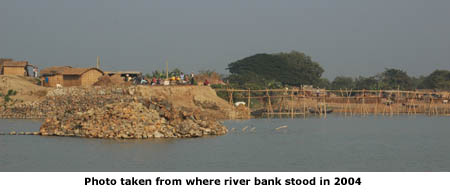

The following day we take a motorized country boat out into Ganga to pay another visit to Kashmiuldalla village on the char lands on the other side . On the way back we stop the boat next to some heads of trees sticking mout above the waves. Kalyan says this marks the spot we moored in 2004.

We have a minute of silent thought about happier times. Then everyone on board starts talking all at once:

"We are like fish without water." Idrish Ahmed.

"Unblock Pagla and allow Ganga to behave normally. You cannot control this river." Monatosh Shah.

"I've lived here all my life. In a few years will Panchanandapur be just a memory?" Tajmal Huq.

Will anything be left when I return?