POSTSCRIPT

Seeing the Ganga at Ganga Sagar

has filled me with hope. I have often felt fearful of Ganga’s future

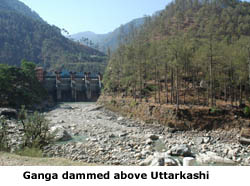

during this yatra. Can she survive Tehri, toxic chemical dumping and Farakka,

the demands of a rapidly developing India? At Ganga Sagar, with its air of

jubilation, the river feels immortal and invincible. But is she really immortal?

Can Ganga die?

The simple answer is yes,

the river can dry up in certain places in the reaches between Haridwar and

Allahabad for a few very simple reasons. Too much water is being taken out

for irrigation or impounded behind dams huge and small to generate electricity

for an economy thirsty for electricity (the problem can only get much, much

worse as India urbanizes; a city dweller uses ten times as much water as a

villager) and though the groundwater does get substantially recharged from

runoff from the Shivalik hills there simply is not enough water coming in

to Ganga to meet all the demands made on her. The Balganga near Kannauj is

the only substantial river in this whole eight hundred kilometre stretch.

And it’s not enough. This is a simple case of supply and demand, and

supply is inadequate.

Indeed, the more I think about the pressures

on Ganga the more I’m convinced we may also be doing everyone a grave

disservice (and everyone means Indians and non-Indians) by only talking about

the river in terms of either mythology or environmentalism. There’s

a word missing - economics.

If you think of the river as an economic resource,

as a raw material then it should become possible to come up with solutions

that can save this resource for future generations. People need water and

they need things that are derived (such as electricity) from water. But there’s

nothing to say electricity can’t be generated from other sources. It

would be nice to save Ganga’s environmental ecology. But all the time

we should have been thinking of the role Ganga plays in economic life. After

all, that’s really why her environment is under such threat. Indians

are starting to ask too much of this river. She needs time to recover before

it’s too late!

If you think of the river as an economic resource,

as a raw material then it should become possible to come up with solutions

that can save this resource for future generations. People need water and

they need things that are derived (such as electricity) from water. But there’s

nothing to say electricity can’t be generated from other sources. It

would be nice to save Ganga’s environmental ecology. But all the time

we should have been thinking of the role Ganga plays in economic life. After

all, that’s really why her environment is under such threat. Indians

are starting to ask too much of this river. She needs time to recover before

it’s too late!

I’d also re-frame the

pollution question. I’m not convinced Ganga will die from pollution.

Yes, pollution from the tanneries in Kanpur is bad, very bad. But pollution

can be mitigated by human agency. Supply can’t. More water would substantially

lessen the pollution problem by diluting the concentration of pollutants and

flushing them away to quieter areas where they deteriorate in tranquil neglect.

(But not toxic heavy metals. Only total prohibition can prevent them.)

I’m not being complacent, just trying

to be realistic. I have many friends and colleagues who’ll be up in

arms and probably never talk to me again because I appear to be minimizing

the dangers of pollution. I’m simply saying Indians can do something

about controlling what goes into the river, but they can’t control how

much water is in there to start with.

Yes, I know there’s always river-linking.

But does anyone seriously think that this will ever come to pass? There are

basic hydrological and geographical reasons why you can’t link river

basins. Another idea, building giant dams in the Nepalese Himalayas isn’t

the answer either. What do you do about the silt washed down by fierce monsoon

rains? Reservoirs have to be at rock bottom before the monsoon, which means

they don’t have enough water to generate electricity or irrigate fields

at precisely the period of year when both are in short supply.

Other ideas such as storing water in vast underground

aquifers such as the Bhabar in the Shivaliks are too futuristic to be taken

seriously. No, if Ganga is not to dry up in stretches less water has to be

taken out, and what water there is needs to be stored better in small check

dams, then used in micro-hydro electric schemes. Or farmers have to find more

profitable and less thirsty crops. Small is still beautiful, no matter how

many times you have to repeat it.

Will this change the status

of the goddess? Can Goddess Ganga survive if the river dries up? Will rituals

wither away?

The last is probably the easiest to answer.

No. Rituals evolve, they’re always evolving. Millions no longer bathe

every morning in Ganga, not just because it may be polluted but because they

no longer have the leisure to do so. Whether you agree or not, the pace of

life even in India is accelerating. I know many city-dwellers who bathe at

home, not in Ganga: they simply add a few drops of Ganga jal to their tap

water. That’s not going to change. For birth and death ceremonies much

the same thing: add a few drops of Ganga jal. Those who believe in the water’s

medicinal powers will continue to drink it, whatever.

But can Goddess Ganga retain her place in people’s

hearts and cosmos if the river shrivels up in places? I see no reason why

not. After all, the river is simply the goddess in liquid form. The important

thing is she is still a generous goddess. If people no longer bathe every

morning she may become less immediate in people’s daily lives, but she

won’t die as a goddess. It’s romantic to link the possible disappearance

of the susu - Ganga’s mount, to the disappearance of the river. But

how many people north of Varanasi have even seen a susu? It’s in their

imagination: actually seeing it won’t diminish the role and place of

Ganga in their hearts.

Indians I respect argue that Ganga has to be

protected because, ‘It gives life so I must protect it. I cannot protect

something unless I respect it, therefore it is sacred.’ Not because

it’s a goddess, but in order to protect Indian society and civilization.

My friend Sharada Nayak in

Delhi goes further. ’Sacred means giving importance to the natural life-giving

substance, to the function. For instance I gaze on a tree that is held to

be sacred: that doesn’t mean that I am worshipping the tree. I am emphasizing

the importance of the tree. Sacred therefore means to me respect for nature.

My friend Sharada Nayak in

Delhi goes further. ’Sacred means giving importance to the natural life-giving

substance, to the function. For instance I gaze on a tree that is held to

be sacred: that doesn’t mean that I am worshipping the tree. I am emphasizing

the importance of the tree. Sacred therefore means to me respect for nature.

‘I am not that religious. But I go all

the time to worship Ganga as the goddess. To me Ganga is sacred, in the sense

that life comes from the land. And anything that happens to nature affects

my living and therefore is sacred. It is my relationship with a life-giving

force. I think all the temples along Ganga reaffirm the sacredness of our

natural heritage. What would happen if all the snows of the Himalayas melt

because of global warming and the rivers cease to flow? The Tehri Dam therefore

hurts me personally.’

I agree with Sharada that taking care of Ganga

should be re-framed as an anguished plea in favour of sustained development,

for trying to live in harmony with their environment. If Indians allow Ganga

the river to be raped and pillaged, it means they are destroying their own

habitat, their own birthright. Ganga is therefore a symbol of that birthright,

a metaphor for India’s future.

‘If ecology and mythology were linked

this could be very powerful,’ Sharada continues, ‘because the

myth grew out of sustaining the land and your dependence on it. This is an

agricultural country. We are very much dependent on the land. The ecology

of the land is woven into our basic mythology.’

Mythology and ecology hand-in-hand. Could belief

in a sacred Ganga translate into respect for nature, and therefore for sustainable

development? You cannot stop development. India needs the energy, the land

needs irrigation. But you can respect it. An awful lot of this debate about

Ganga anyway is probably not really about mythology at all. It’s basically

people fighting over an economic resource. Ganga is indeed a symbol in the

debate of rape versus respect of nature, about the misuse of resources, the

loss of respect for the river as life-giver, of its irreparable effect on

the lives of people. Destroy Ganga and you will therefore destroy the essence

of India.

The greatest danger to the

river comes from the goddess herself. I believe that the faith in the ability

of goddess Ganga to cure herself leads to avoiding the life and death issues

the river faces.

I think the other threat to the goddess may

be less from within India than from outside India. I worry that India may

be changing too fast. Like many others I worry that these changes may not

take into account the delicate fabric of traditional and rural India.

I used to think none of this would really matter.

India has suffered many physical and cultural invasions down through the centuries

- Aryans, Moghuls, British - and in each case bent and absorbed them, ‘Indianizing’

them. It’s a comforting scenario, part and parcel of the Indian concept

of circular time. But what if it doesn’t work this time? There’s

no law of physics that states time must always be circular, that it can never

experience a linear deviation. Can one go too far, beyond the point of no

return? Can the river Ganga effectively die?

How to convince those who worship the goddess

that the physical deterioration of the river can affect her essence?

It may be possible, but it will require ordinary

Indians to make that link, not just the members of its elite or outsiders.