REPORTER'S NOTEBOOK

If you’ve never been

to a really big mela, it’s a bit like an open-air rock concert at the

edge of the sea, but with two important differences - no entrance fee and

no age restrictions. Nobody advertises the mela. It just is. Everybody knows.

You just get there anyway you can - by train, by bus, by foot. And once you’re

there you can sleep anywhere you can find, wash, eat, chat, meet people, sing

bhajans, visit stalls selling just about everything - conch shells, beads,

books, cassettes, even DVDs. At the mela at Ganga Sagar the only thing that

is fixed and immutable is that on the  great day you take your ‘holy

dip’. Precisely when is a bit more problematical.

great day you take your ‘holy

dip’. Precisely when is a bit more problematical.

I know some Kolkata socialites who’ve

travelled to Sagar for past Makar Sankrantis from Kolkata by motor launch.

But they were VIPs and guests of the government. Ordinary people have to take

the ferry across from Kakdwip. We’re not quite ordinary, but neither

are we special. However, we do need to take the Scorpio across and find somewhere

to stay where our recording equipment will be safe and we can recharge batteries.

The hotel has been completely booked by VIPs for many months. We go to Alipore

to see Mr Choudhary, the Additional District Magistrate of 24 South Parganas.

Letters are typed and signed; a pass for us and the Scorpio. ‘ Go to

the mela office as soon as you arrive. They will look after your accommodation.’

Go to

the mela office as soon as you arrive. They will look after your accommodation.’

We (Raja, Bijoy, James Ashby and myself - Martine

has returned to the USA to deal with a fiscal deadline) leave early to get

there before the crowds. Fat chance! The Prime Minister is in town, so most

of the main roads in Alipore have become one-way overnight. Round and round

in circles till we finally get out of the city. But it’s a lovely winter’s

day with very little traffic. We’re aiming to reach the loading bay

at Kakdwip by 2 pm, so we can get to the mela grounds while it is still light.

But when we get to Bay No.

8 at Kakdwip we find half of India already there (where did they come from?),

and no ferry. Why the delay? Tides! We’ve missed high tide by thirty

minutes. Now the water in the straits is so low the ferries can’t load.

They’re stranded on the beach like exhausted, snub-nosed whales covered

in mud and oil. We will have to wait another six hours. So we read, walk,

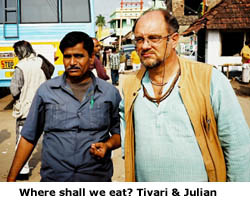

and eat - samosas, pakoras, fresh coconut juice. When in doubt follow the

driver, Tivari has always known where to eat!

Finally we reach the other side, along with

thousands of other Indians. We drive off in our Scorpio. They are herded on

to buses. But the destination is the same - Ganga Sagar, the spot where Ganga

and the sea finally merge. Good roads, little traffic. Suddenly we cross a

bridge and enter an immense fairground. Or is it a film set? Floodlights as

far as the eye can see. And who is waiting for us but Mr Choudhary from Alipore,

transformed into Mela Officer, holding court in a small house on the outskirts

of Sagar City. Another chit is signed: ‘Go to the Information Tower

and give this to DICO.’ An attractive young woman called Malvika Goswami

- the District Information an d Cultural Officer - is waiting to show us to

our quarters as members of the media. It appears we are the only firangs.

d Cultural Officer - is waiting to show us to

our quarters as members of the media. It appears we are the only firangs.

We cross a broad avenue of

loose sand and dart between two stalls, left down an alleyway, to our new

home - individual bamboo and Ganga grass thatched huts with verandah, bedroom,

open-air shower and latrine. One lock, one chair, one bucket, one blanket,

one electric light, one solid wooden bed - all enclosed by a wall  of Ganga

grass to keep curious eyes out.

of Ganga

grass to keep curious eyes out.

There’s a particularly

noisy generator at the end of our block, doubtless powering the floodlights

and the bulbs in all the stalls that front the avenue leading to the water.

Throughout the night, a continuous stream of pilgrims shuffles down past our

huts to the sea, to take a dip, chat and then come back, stopping to buy conch

shells and other souvenirs at these stalls. Some fall asleep on the sand in

this broad avenue. Others head off to other areas in mela city - it’s

all signposted by block. At the h ead of the avenue is the only solid permanent

structure - Rishi Kapil Muni’s temple.

ead of the avenue is the only solid permanent

structure - Rishi Kapil Muni’s temple.

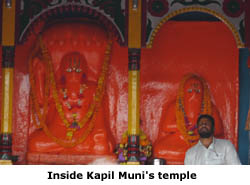

It’s not the original

by any means. The spot where the sage meditated is now way out to sea under

the advancing tide. Inside the temple are three stone images: Kapil Muni himself,

eyes wide open, looking out to sea with thousands of devotees waiting on his

every word, with Ganga and King Sagar flanking him. The horse of the sacrificial

yagna, which caused all the problems in the first place, stands off to one

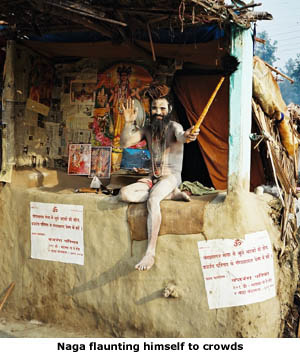

side. Next to the temple are rows of tiny stalls. Inside sit naked nagas,

bodies smeared in ash, vaunting the size of their penises in proportion to

the charms of female pilgrims (especially any foreign tourists) who have to

pass their gauntlet to get to the temple and the sea. I ask Raja if the ash

has some religious significance. After all Catholics smear their foreheads

with ash at the start of Lent  to signify that man comes from dust and will

return to dust.

to signify that man comes from dust and will

return to dust.

‘No man, it’s to keep warm! Smearing

ash locks body heat in.’

‘Oh!’

So apparently does mud, which may explain another

image that has haunted me for several years. In 2001, I watched as a man above

Asi Ghat in Varanasi sat in what passed for the Asi stream and slathered himself

with black mud. At the time this seemed the height of madness: that ooze was

probably toxic, certainly full of pathogens. But maybe that wasn’t the

point?

Gazing at this vast scene, trite thoughts come

to mind: this is truly a mela! Not for the tourists or the Indian middle classes.

Definitely not a media event. Of the people, for the people, by the people!

Next morning Jeeta Babu is

seated on a mat, holding court in the middle of the avenue just behind our

compound. His fifteen-foot long tresses, like hawsers on a ship, are stretched

out in front of him. ‘I don’t want to talk with you! I know all

about you.’ Not for the first time microphones are mistaken for cameras.

‘You will get a lot of money for my photo,

won’t you? I won’t give anything.’

Raja asks,’How much money do you want?’

Jeeta Babu is adamant. I can’t blame him.

‘No, I won’t give it.’

Raja tries flattery. I’m staying well

out of this fawning. It won’t work, I know it.

‘You know everything - you have such huge

hair. You are a great man with great thoughts. ’

‘Yes, I also think so!’

Raja doesn’t know when to stop: ‘This

is a place for saints and peace.’

‘Yes I am for all people - but not for

you.’

‘Yes I am for all people - but not for

you.’

No point in flogging a dead horse. Time to move

on. I sympathize with Jeeta Babu. Of course, he’s been spoilt by media

attention up in Kolkata. His photo was in The Telegraph earlier this week.

Now he will only talk with a substantial down payment.

Just behind Jeeta Babu are

a group of some fifty peasants wrapped in winter woolens, sitting on the sand

under the Information Tower, bundles around them, waiting for one of their

group to turn up so they can leave the island. Most of them work carving temples

in Udaipur. Their leader is Dhan Singh Kumaut.

‘This is our pilgrimage. We will complete

it and then we will go home. We came yesterday. We’ve already taken

our bath. We leave tomorrow evening.’

In fact they left Udaipur by bus back on December

27th. They’re taking six weeks off from work to go on a yatra around

the entire country. They’ve already been to Haridwar and Rishikesh.

After this they’ll head south to Tirupati, Kanyakumari and Rameshwaram

endin g up in Dwarka.

g up in Dwarka.

It’s a long way from Udaipur. ‘Why

do you make a yatra like this? Purely for religious reasons?’

‘We come to see the gods and goddesses

and worship them.’ But there’s also another very important reason.

‘In this way we’ll meet people on this journey. So yes, it’s

also about meeting people. And it gives peace to the soul.’ What’s

important to them is just being here, seeing where Ganga has washed over the

ashes of Sagar’s sixty thousand sons, and discovering their country

and countrymen. A wonderful reason to make the journey.

But one of the group is missing; the group need

to catch the ferry and get to Kolkata tonight so they can take the train back

to Rajasthan. ‘We have informed the Information Centre.’ That’s

why they’re sitting here, waiting till the missing villager shows up.

In the Watch Tower behind us the P/A is appealing to the missing person -

Ganesh Pal - to come quickly. But another villager says there’s no need

to worry: ‘He will come here after wandering around.’

villager says there’s no need

to worry: ‘He will come here after wandering around.’

Here on the beach everyone wants

to tell me his or her life history. Kailash Baba, for instance, lives on the

banks of the Sipra river near Ujjain He’s done the entire parikrama

of the Narmada twice. (‘Two circles, two thousand, six hundred and eighty

kilometres of the Narmada is the pilgrimage. I’ve done it twice.’)

He walked here from Nasik. After Ganga Sagar he’s off to the Kamakshi

temple near Guwahati in Assam - a long yatra. You name it, he’s been

everywhere: Gaumukh, Gangotri, Haridwar, Allahabad, three times alone to Shiva’s

cave at Amarnath in the Himalayas. And with just a bundle on a stick slung

over his shoulder.

‘These are all your worldly possessions,

I take it, you have on you?’ I ask.

‘This is bedding to lie down on; this

is my blanket. That’s all I have. If I get some food, that’s OK.

And there’s always water from Ganga’

Tulsi Ram is burly, with close-cropped hair.

He’s dressed in a white kurta with an orange scarf. He comes from Mathura-Brindavan.

‘Varsana, to be precise. Radha also comes from Varsana.’ (Note

the present tense.) ‘We call it Brij - the leela area - the playground

of Krishna and Radha. My ancestors were friends of Krishna.’ (Another

wonderful example of how time collapses - it’s the event that is the

defining factor. When is unimportant.) We’re related to a friend of

Krishna’s - Sudama.’

Tulsi Ram also says that tonight something wonderful

will happen: ‘There will be a rain of amrit. That’s why it’s

auspicious to bathe here. People will come from India and all corners of the

world. The gods will drop a rain of nectar here on this area tomorrow, for

the welfare of all the believers. Our souls will be released. This is why

this day is so important.’ So when will Tulsi Ram take his bath? ‘Six

o’clock, as soon as the sun god comes up.’ (I store that away

for future reference.)

Meanwhile, the tide is starting to come in.

As if on cue, a group of villagers seated on the sand starts chanting ‘Radhe, Radhe.’ One of them wanders off, starts playing small cymbals, singing a bhajan to Krishna. Meanwhile, a brass band advances across the beach, preceding a village deity carried on a palanquin, conch shells blowing and women ululating. A hundred yards offshore, a large hovercraft is crisscrossing the bathing area. A Kashmiri terrorist group is reported to have threatened to attack bathers on Makar Sankranti, so the army is taking no chances.

Two women - Babli Jha and

Pramila Mishra from Patna, are doing something odd, scooping sand into a plastic

bag. Not for sandcastles, I think.

‘We will mix it in the foundations of

our houses so our new houses will be blessed,’ they tell me. The thought

had not occurred to me.

Equally odd: why are so many calves on the beach?

Raja is astonished I don’t know the significance.

‘Gou daan - this is for gou daan (donation

of the cow to the puja). You should touch its tail.‘Then you will go

to the next world.’ ‘How?’ I ask.

Raja mutters, ‘This is Baitarini.’

Baitarini is an actual river in Orissa that

is mentioned in several myths in the Ramayana. The devotees here at Ganga

Sagar tell Raja that the waters of the Baitarini are red and its source looks

like a cow’s face. In Hindu mythology Baitarini is the river of life

which you cross to get to the next world. So a cow with its tail painted red

is the symbol of this river. If you catch its tail and take a few steps into

the surf you’re saved. Yet another way to be saved! Raja’s disappointed

I don’t want to perform the ritual. The man leading the calf is not

amused either.

The band is returning down the beach. It’s

probably time to leave and go back up past Kapil Muni’s temple, brave

the nagas, and find somewhere to eat. The tide washes over the pooja offerings

- flowers, sticks of incense, pieces of coconut.

That night I never see a rain

of amrit, not even a mist. I don’t get too much sleep anyway. No one

else can have slept either. The PA system from the Information Tower blares

throughout the night. If there is an official start to the great day, I miss

it. The guidebooks say the priest (which one? From the mandir?) announces

the auspicious moment has arrived and the crowds surge forward chanting ‘Kapil

Muni ki jai’ and plunge into the sea. This may have happened. But that’s

not what I witness.

I peer out at three in the morning. The tide

is so far out and the beach so shallow you have to walk half a mile out before

it ever reaches over your head. Crowds are indeed bathing to chants of Gangaji.

There are also a lot of calves in evidence (mooing in protest or in prayer?),

brass cymbals beating rhythmically on the beach, and everywhere lots of people

talking, having a good time. A night out at the seaside. The conch shell stores

are doing brisk business. I pad back to my bed.

Up again at six o’clock, in expectation

of something momentous. Malvika Goswami, the Cultural Liaison Officer, told

me yesterday, ‘The auspicious time is ten minutes before sunrise till

ten minutes after. A window between six sixteen and six thirty six.’

But nothing seems to have changed much since

my earlier sortie. The tide is still way out. To get to the sea one has to

walk a long way. Same PA blaring, same cows, same clappers, same crowds -

well, they do seem greater. Groups of women are seated on the dry sand near

the Behula and Lakhindar pandals singing bhajans. So many people. Someone

tells me huge crowds have arrived during the night. They surge down the avenue

towards the sea. Village pandits are chanting ‘sab teerth baar baar,

Ganga Sargar ek bar.’

One group of villagers, swaddled

in thick woollens, shuffle in lockstep, held together with a thick rope tied

round their perimeter so no one will get lost on land or at sea. It’s

possibly the one and only time they have seen the sea, except on the ferry

across. Certainly their first time actually in the sea: and all this less

than three weeks after the tsunami. No wonder they look bewildered and apprehensive,

while all around them there’s a raucous cacophony of spontaneous joy.

Conversations with bathers are necessarily brief.

Why get in their way? One fully-dressed man mummified in layers of woollens

is watching the bathers to see how they do it. He says he lives on the island.

Strange to think you could live here and not know all the rituals - the mantras

and the turning seven times in the water. But there has to be a first time

for anything and everything.

A man from Chhapra in Bihar has just come out

and looks very cold. ‘Yes, I’m shivering a little bit. After you

have a bath when you come out you always shiver. It’s the air that’s

cold. But the water is warm. (This is true; when you bathe in the morning,

water always feels warm because of the contrast with the outside temperature.)

It’s my first time, and I wouldn’t miss this for the world. This

bath is very important!’

A husband and wife are scavenging

discarded coconut shells at the water’s edge, obviously offerings to

Ganga left only an hour ago. Is there any fruit left inside? If yes, they’ll

take them back home to resell. They’re quite unashamed about it. In

the city or in the West that would be a big scandal. Dirty, sign of poverty.

Here at the mela it’s so normal no one even thinks twice.

A boy has a pile of green coconuts on a handcart:

‘Fifty paisa. Need to make an offering? Coconuts. Fifty paisa.’

A villager asks: ‘Do you have any daab - green ones?’ They’re

cheaper.

Three women from Nagpur are raking the wet sand.

‘I’m picking up the coins that were

offered to the sea,’ one tells me. I ask her how much she’ll make.

‘Oh about twenty-thirty rupees. Something

like that.’

No trumpets this morning, just big bass dhols

banging rhythmically away, up and down the beach. A quick sample of bathers

suggests the net has been cast pretty wide - Agra, Delhi, Nepal. All of them

say the same thing: ‘This is the most important day of the year. If

I take holy dip here, it will purify me and bring me closer to God.’

A family from Mienpuri in Uttar Pradesh spontaneously

burst into a round, each one singing a different line:

‘This is about Kapil Muni maharaj. He

had done a meditation over here. And all the sons of Raja Sagar, they had

been burnt to ashes over here.’ (soprano)

‘He had given a curse.’ (mezzo)

‘And the Ganga is also here , and she…’

(alto)

‘Raja Bhagirath , he had done the meditation

here standing on one leg...’ (tenor)

‘And it is known as Ganga bath...’

(baritone)

‘Sagar’s sons they get back their

life... the Bhagirath brought the Ganga here.’ (bass)

And on and on it goes.

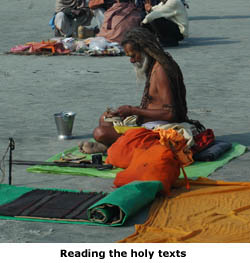

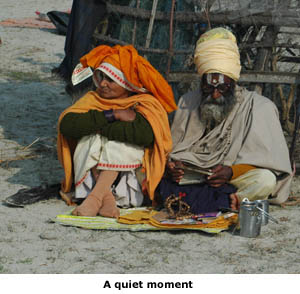

Two elderly swamis are holding

court on the sand. They have come from Jharkhand, complete with trishul and

bell. They’re playing on a dumroo - a small drum that’s played

in one hand, with a string tied to the middle and beads at either end. When

you shake it the beads hit the drum part and make the sound.

Two elderly swamis are holding

court on the sand. They have come from Jharkhand, complete with trishul and

bell. They’re playing on a dumroo - a small drum that’s played

in one hand, with a string tied to the middle and beads at either end. When

you shake it the beads hit the drum part and make the sound.

They bathed at four in the morning, spent an

hour praying, and now they’re ready to talk world peace to all and sundry.

One rings a bell, then the dumroo, which is attached halfway down the trishul.

His colleague then blows on the conch and they begin chanting ‘Ganga,

Ganga.’

Raja, trying to be helpful, asks them about

Makar Sankranti. One of them starts telling the story rather well. His colleague

interrupts and goes off on a tangent about a river called Ulta Ganga (which

exists in West Bengal): ‘Normally the Ganga flows from west to east.

But here on this day it is flowing the other way. It is Ulta Ganga. It flows

the other way and at night.’ (The most extraordinary stories get told

here!) They start arguing - verbally, then physically.

‘I’m telling him about Makar Sankranti.

I won’t move. I’ve planted my flag here..’

‘I’ll cut off your....’

‘What do mean? You’ll cut off my...’

A policeman appears from nowhere, tells them

to leave. ‘Come on you two, break it up. Or off to the thana.’

Raja doesn’t bathe or go into mandirs.

He’s been depressed much of this trip. But he’s visibly energized

today: ‘I just can’t believe such a big bath. Amazing. People

are crazy or we are crazy.’

Tivari returns from bathing.

If Sagar’s sons can get back their lives then we all can. Here on the

beach at six thirty in the morning on Makar Sankranti, we look back at our

many months spent together on Ganga. We’re nearing the end of this yatra

down Ganga. But I think both of us also realise this could also be the swan

song of a working relationship that’s lasted now twenty years.

‘This is the end of our yatra,’

I say.

‘Yes this is the end.’ He looks

suddenly solemn, almost sad.

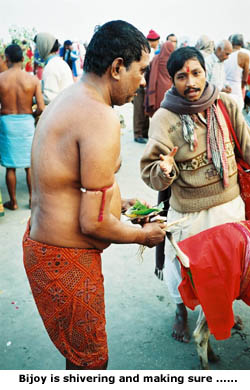

I ask Bijoy which has been the single most memorable occasion on this trip.

He thinks a few minutes, lists all the tirthas he bathed at.

‘Which one? Actually each place has its own significance. But the most

important was Prayag. This is also a very important and historical tirtha.

That’s why people come because they believe that their souls will be

freed if they have a bath here.’

Shivering, Bijoy looks seriously at me:

‘Chief, what a great journey we have

made.’

Indeed we have. It’s hard not to think

in clichés. This really is an extraordinary mass of humanity: the whole

of India really does seem to be here. Fitting that our yatra down Ganga should

end here on this day. I really wouldn’t have missed this for the world.

We have to pack up and get back to the ferry,

the mainland and Kolkata. Slowly and reluctantly I move away back to the dry

sand. I cross the path of a man rattling off the names of gods - great and

small. The mobile phone rings.

‘Hello. Who is it?’

‘It’s Martine, your wife. Calling

from America. Remember me? I need to check something on your Visa bill.’

‘Can you phone back later?’ I tell

her. ‘It’s Makar Sankranti. I need a few moments alone. It’s

the end of a wonderful journey.’