Varanasi

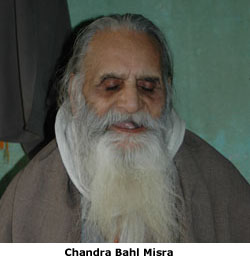

For Chandra Bahl the answer is simple: ‘Ganga has a dual identity. If

you consider her as a river then she can be polluted and die. But if you consider

her as goddess then she can never die. Pollution is in the eye of the beholder.

If you believe, you cannot get sick and there is no pollution.  There are no

mass epidemics and Indians are not fools, so how does the West explain this?

The West should ponder this.’

There are no

mass epidemics and Indians are not fools, so how does the West explain this?

The West should ponder this.’

For millions of Hindus, Ganga can therefore never be dirty in the Western

sense of pollution. For them physical pollution and spiritual pollution are

two entirely different creatures. Only the most intellectually sophisticated

attempt to make a possible connection; to argue that severe physical pollution

might affect the spiritual purity of the goddess.

In Kanpur rituals have been modified. But ‘modify’ does not mean

undermining the sanctity of the river as goddess. A mother might fall on hard

times but she will still be a mother, you don’t disown her. A woman

can still be a queen even if she is in rags and physically filthy. She retains

her underlying grace. Similarly with a river.

As the judge says: ‘The river is simply the goddess in liquid form.

No matter how much the physical river is abused she still retains her sanctity.

All the evidence suggests she will  always be revered. This is the feeling

these people have for Ganga.’

always be revered. This is the feeling

these people have for Ganga.’

We reluctantly leave for Sitamahri, midway between Allahabad and Varanasi

- another tirtha known primarily to Tivari. The next morning, out on the bluffs

overlooking the river, I notice the river being used for commerce for the

first time. Boats bring down sand from upstream, unload it into wicker baskets

that camels then gracefull y carry up the bank to waiting lorries to be driven

away to area building sites.

y carry up the bank to waiting lorries to be driven

away to area building sites.

Indu arrives in Varanasi tomorrow.

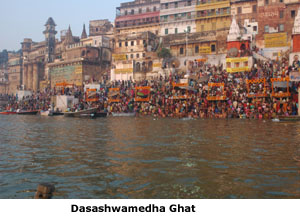

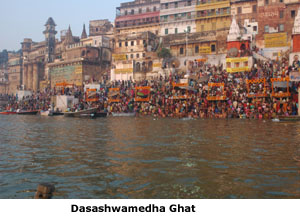

Varanasi, also known as Banaras, Benares, or Kashi,

is situated on the left bank of Ganga, where the river flows north. In Hindu

culture this signifies a daughter returning to her father’s house, a

most auspicious event. This is probably why it is the holiest of all stops

along Ganga, more so than the Sangam or any of the other major tirthas.

Varanasi is loaded down with myths, not the least of which is the common conception

of how old it really is. It is often called the world’s oldest continuously

inhabited city. While it is technically true that people have lived on or

near this spot for many thousands of years, it still strikes me as intellectually

lazy because it is taken too much on unquestioned trust. No matter what its

age, there is no doubt this is India’s holiest city, because it is believed

to be the city of Shiva on earth, and because it flows north.

Why do people come to die at Varanasi? What’s so special about death

here at Varanasi?

Death in Varanasi is moksha, liberation. If one dies here, Lord Shiva himself

will whisper the Tarika mantra, the boat mantra, the mantra that will take

you across the ford to the far shore. That is Shiva’s promise, that

everyone who dies in Varanasi will  be liberated from the endless rou

be liberated from the endless rou nd of

birth and death that makes up the cycle of life. Sounds a good reason to me.

nd of

birth and death that makes up the cycle of life. Sounds a good reason to me.

So people come from all over India to die here because from one can bypass

the hell of endless reincarnation. Devaprayag, Haridwar, Allahabad, Gays,

Ujjain, Nasik, Ganga Sagar and others are all very important in purifying

the human soul of sin and conveying one’s remains to the next world.

But at Varanasi-Banaras-Kashi you can cut out all the waiting and go direct.

A trip one early morning on a country boat

with Anil and Rinku, our boatmen, shows why Varanasi makes such a huge impression.

For at least the last three hundred years visitors have found scenes of mourning,

bathing along the river Ganga visually and emotionally arresting. It’s

the sheer size of the ghats at Varanasi - a gentle arc of three miles on tall

bluffs.

Can a Western visitor ever really understand

this mixture of the sacred and profane, of life and death that is the essence

of life in this very public, and very Indian arena called Varanasi? And everywhere

human life in noisy motion. People a re performing their religious ablutions,

others are simply scrubbing down with soap and shampoo.

re performing their religious ablutions,

others are simply scrubbing down with soap and shampoo.

Long flights of stone ghats lead down to the

river, crammed with thousands upon thousands of Hindus going about their morning

prayers waist deep in the river. Hands cupped, eyes closed, they pray to Ganga, Surya, to Shiva, Vishnu and

many more besides, letting the water of Ganga dribble through the palms of

their hands. The bather then turns seven times clockwise and dunks him or

herself thrice in the river. The ritual completed, they dry themselves, get

dressed and chat with their neighbours before mounting back up the ghats and

to home, breakfast and the day ahead. Most Westerners simply have never seen

anything like this: massive morning prayer along the river Ganga.

Everything about Hinduism is a head-on challenge

to Western notions of religion and God. How many times have Westerners (and

Muslims) poked fun at the notion of thirty or three hundred million gods?

Fixation on a precise number misses the point. Hindus are expressing the idea

that God is infinite, that whatever they mean by God cannot be captured by

any one idea, name or form. Thirty or three hundred or three million is merely

another way of saying you can’t count the ways in which God can be present.

For Christians, Muslims or Jews, brought up to regard all forms of idolatry

as heresy, this public display of bathing, faith and jubilation is therefore

profoundly unsettling.

Same problem at Harishchandra and Manikarnika Ghats, the two cremation grounds,

smack bang in the middle of the huge crescent of ghats, in full public view.

This is something quite frankly that most people who have grown up in European

and American cultures have simply never seen., where death is carefully hidden

away in professional crematoriums and mortuaries. Indians, on the other hand,

make a very public display of death. They bring their newly dead, wrapped

in cloth, strung between bamboo litters carried through the crowded streets

to the edge of the water. A cremation pyre is built, the body bathed in Ganga

and then for several hours it will burn while relatives and priests chant

and perform the prescribed rituals. In Varanasi death is the essence of the

public life of the city. That is what makes it powerful. This is also what

makes it often incomprehensible to people seeing the city for the first time.

Same problem at Harishchandra and Manikarnika Ghats, the two cremation grounds,

smack bang in the middle of the huge crescent of ghats, in full public view.

This is something quite frankly that most people who have grown up in European

and American cultures have simply never seen., where death is carefully hidden

away in professional crematoriums and mortuaries. Indians, on the other hand,

make a very public display of death. They bring their newly dead, wrapped

in cloth, strung between bamboo litters carried through the crowded streets

to the edge of the water. A cremation pyre is built, the body bathed in Ganga

and then for several hours it will burn while relatives and priests chant

and perform the prescribed rituals. In Varanasi death is the essence of the

public life of the city. That is what makes it powerful. This is also what

makes it often incomprehensible to people seeing the city for the first time.

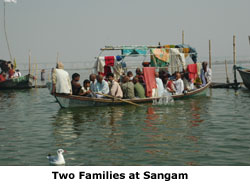

Anil and Rinku row across the river to the largely deserted south bank, which

isn’t sacred. Rama Kanth Katheria is bathing there with his entire family,

all ten of them.

Rama Kanth is voluble. He explains that few people ever cross to bathe on

this Maghar bank: ‘It has not been blessed by the gods. But we come

here anyway because it is quiet and clean. Yes, our sins are washed away,

but we have so many that are invisible, from previous lives. Today I have

taken a sankalp (vow) to give up some vices and bad friends.’

Next morning, Rana B Singh introduces me to his family purohit or panda,

Devendra Nath Tripathi, sitting less than five yards away. Tripathi intones

mantras for his customers at his stand here at the head of Asi Ghat. He gives

them tulsi leaves, which he has blessed: they hand him coins, fruits and vegetables

in return. Tripathi explains: ‘Many women come here to make offerings

before bathing. They make a sankalp and set their goals for the day. In return

I bless them with a mantra.’

The first couple have come to seek his blessing for their nitya pooja - the

daily bathing ritual. They hand him fresh fruit and a few coins. Tripathi

begins the mantra. It starts off listing time and place in descending order

- Cosmos, India, Varanasi, Asi Ghat, month, day, name of the family - then

purpose (take a daily bath in Ganga). Next, an appeal to Mother Ganga, then

one to Vishnu to help one get through the day. The devotees give a symbolic

offering of fruit as proof of their good faith and Tripathi in return takes

tulsi leaves, while they touch Tripathi’s feet. This is the proof that

they have performed the initiation rite

The first couple have come to seek his blessing for their nitya pooja - the

daily bathing ritual. They hand him fresh fruit and a few coins. Tripathi

begins the mantra. It starts off listing time and place in descending order

- Cosmos, India, Varanasi, Asi Ghat, month, day, name of the family - then

purpose (take a daily bath in Ganga). Next, an appeal to Mother Ganga, then

one to Vishnu to help one get through the day. The devotees give a symbolic

offering of fruit as proof of their good faith and Tripathi in return takes

tulsi leaves, while they touch Tripathi’s feet. This is the proof that

they have performed the initiation rite . Tripathi blesses them: ‘With

the blessings of God you may now perform the rite.’

. Tripathi blesses them: ‘With

the blessings of God you may now perform the rite.’

The whole thing has taken barely three minutes from start to finish. This

is the simplest of all daily rituals. When the women have bathed they will

return to seek more blessings from Tripathi, because without them the dip

is incomplete. Again, they will give offerings to the gods - Rama, Krishna,

Vishnu - offer water to Tripathi’s basil plant and then make another

sankalp for the day ahead.

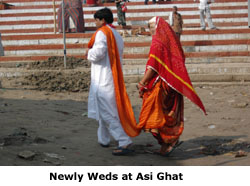

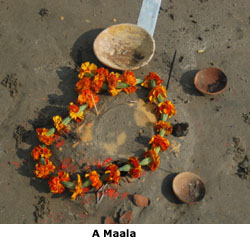

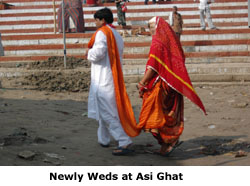

Down at the river bank, a wedding party is preparing to clamber into a boat.

The newly-married couple have come to ask for Ganga’s blessings, so

they are offering a garland to Ganga. The party will do a little pooja on

the far bank and then come back. As one of them explains: ‘Ganga is

our mother so we ask for her blessing, for their good married life. Before

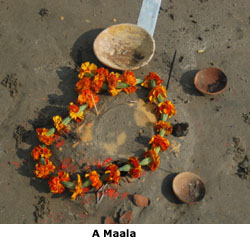

she climbs in the boat, Renuka ties a garland of flowers to the prow of the

boat. ‘This is the maala.

We’ll leave it over there after the pooja.’

the boat, Renuka ties a garland of flowers to the prow of the

boat. ‘This is the maala.

We’ll leave it over there after the pooja.’

Next to the boat, women at the water’s edge are offering sarees to Ganga

for her blessing. ‘We are offering sarees to Ganga and the saree has

come from my brothers’ house. We can do it any time. It’s not

any specific day but we all decided to come here today and do the pooja.’

Why don’t they bury their flower offerings instead of throwing them

into the river? ‘No, all that doesn’t work for us. We have this

way of doing the ritual and that’s it.’ Another couple of women

are bottling Ganga jal to take home for the ceremonial first bricks in the

family’s new home. They’ll mix some drops in with the cement.

In so many ways Ganga is a patron saint who watches over every aspect of daily

life. For all these people the idea of the pollution of the river is regrettable

but it is only a physical blemish that cannot diminish the overall powers

of the goddess. They see no need to make a connection between the physical

and the metaphysical.

Kedar Ghat is full of South Indians washing dishes and bathing.

Kusima is saying her mantra first to the gods, then to the different worlds

- gods, humans, animals - and finally to Ganga. Kusima has come here from

Hyderabad with her mother, sister-in-law and brother. This is probably the

greatest moment in their lives. And the proximity of the Harishchandra cremation

Ghat next door has inspired her: she now wishes to be  cremated here.

cremated here.

Kusima says: ‘’We have seen God, we got a glimpse of the Lord

and bathed in Ganga. Ganga is the ultimate event in my life. We attain salvation

because we have bathed here in Ganga. No other river will do. Cauvery and

Godavari are holy, but Ganga is Divine. Only Ganga comes from Heaven.’

Others in the Tamil community are also in ecstasy: ‘For three generations

no one in my family has had the opportunity. So this visit is very important.’

Literally, the opportunity of a lifetime.

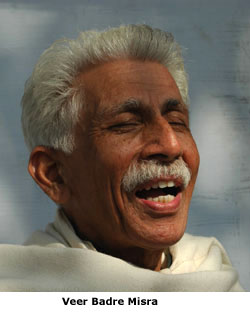

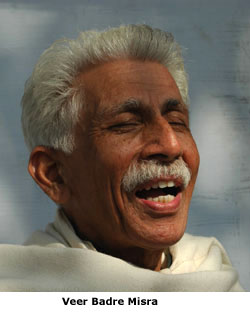

Anil unloads us at Tulsidas Ghat, a hundred yards upstream of Asi Ghat where

we are also staying. Tulsidas Ghat is also the home of Veer Badre Mishra,

the mahant or hereditary priest of the Sankat Mochan temple at Tulsidas Ghat.

He’s spent the past thirty years trying to alert people to the threats

to Ganga here at Varanasi. Until recently, he was professor of hydrology at

the nearby Benaras Hindu University. His Sankat Mochan Foundation is internationally

synonymous with Ganga. The foundation has highlighted extraordinarily high

levels of E.coli in the river: he tells Indians and the world that this makes

it totally unsafe for bathing.

How can VMB spend so much time criticizing the government for its failure

to clean up Ganga at Varanasi” And yet bathe in the river every morning,

all the while knowing as a scientist it’s polluted? How does he reconcile

the two?

Isn’t there a contradiction? I’d expect the mahant to remind me

that a river be both dirty yet clean human souls.

His initial answer surprises me.

‘As a scientist I don’t find anything which can prove that Ganga

has self purifying capacity more tha n any other water mass.’

n any other water mass.’

But he then makes the same distinction as the blind judge in Allahabad. The

metaphysical and the physical worlds are entirely different. ‘Yes, the

river can be poisoned and make people sick. On a purely religious level it

is nectar.

“But can’t poison and nectar mix?’

‘No, the two are entirely separate. I am committed to both Gangas. As

a scientifically-trained mind I want to protect the river. But my heart has

an entirely different relationship to Ganga. The physical world and the world

beyond the limits of our senses are two entirely different worlds.’

So can faith make polluted water clean?

‘Let practising Hindus believe. Let them live the way they want to live.

For me they are jewels who have preserved this culture for thousands of years.

But they are also human beings and it is a proven fact that if one takes polluted

water one will become sick and some will die. And if Hindus die then with

them, this Indian culture and faith will go. The two are related. Can we not

just see this and use all the resources of faith, science, technology and

politics to protect this body of fresh water?’

REPORTER'S NOTEBOOK

REPORTER'S NOTEBOOK  ice ghats.

ice ghats. n to live in Jajmao, near the tanneries.

n to live in Jajmao, near the tanneries. nown it was

this simple to make him so happy I’d have bathed in Ganga a lot sooner!

nown it was

this simple to make him so happy I’d have bathed in Ganga a lot sooner! or go along and hope no one

says anything. In the end he opts to show us round.

or go along and hope no one

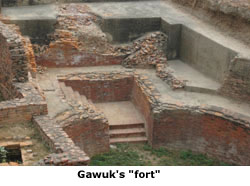

says anything. In the end he opts to show us round.  bathers. The villagers, of course, will always believe it is a site from the

Ramayana.

bathers. The villagers, of course, will always believe it is a site from the

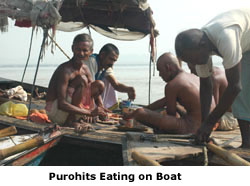

Ramayana. er pandas hurry

him along. They want to finish the ceremony, go off home, and eat.

er pandas hurry

him along. They want to finish the ceremony, go off home, and eat.  Manoj in 2001, in

slightly unusual circumstances.

Manoj in 2001, in

slightly unusual circumstances.  nskrit and Awadhi, so Bijoy has picked him up

as we drive through

nskrit and Awadhi, so Bijoy has picked him up

as we drive through  where the panda with his family

records could be found.

where the panda with his family

records could be found. I know somewhere quiet on the Naini road on the other side.’

Manoj replies.

I know somewhere quiet on the Naini road on the other side.’

Manoj replies. ot?’ I say.

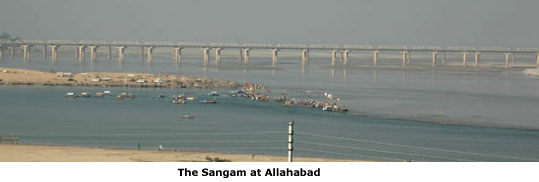

ot?’ I say. but different colours. Yamuna is green and Ganga is

white. While it is called Ganga until the sea, the colour is that of Yamuna.’

but different colours. Yamuna is green and Ganga is

white. While it is called Ganga until the sea, the colour is that of Yamuna.’ gull at the

Sangam!’

gull at the

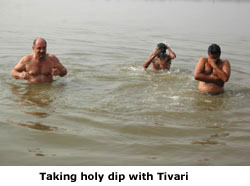

Sangam!’ immediate agenda: ‘I’m going to have a bath. Tivari

will be very upset if I don’t.’

immediate agenda: ‘I’m going to have a bath. Tivari

will be very upset if I don’t.’ up to waist line . So it’s ok.’

up to waist line . So it’s ok.’ ave managed to stay faithful to the shastras (holy

books). We feel good inside because we are going along with Hindu culture.’

ave managed to stay faithful to the shastras (holy

books). We feel good inside because we are going along with Hindu culture.’ offers a third observation full of contradictions:

offers a third observation full of contradictions: is our belief that nobody can finish this river, even this Tehri

dam. Ganga is eternal.’

is our belief that nobody can finish this river, even this Tehri

dam. Ganga is eternal.’ There are no

mass epidemics and Indians are not fools, so how does the West explain this?

The West should ponder this.’

There are no

mass epidemics and Indians are not fools, so how does the West explain this?

The West should ponder this.’ always be revered. This is the feeling

these people have for Ganga.’

always be revered. This is the feeling

these people have for Ganga.’ y carry up the bank to waiting lorries to be driven

away to area building sites.

y carry up the bank to waiting lorries to be driven

away to area building sites. be liberated from the endless rou

be liberated from the endless rou nd of

birth and death that makes up the cycle of life. Sounds a good reason to me.

nd of

birth and death that makes up the cycle of life. Sounds a good reason to me. re performing their religious ablutions,

others are simply scrubbing down with soap and shampoo.

re performing their religious ablutions,

others are simply scrubbing down with soap and shampoo.

Same problem at Harishchandra and Manikarnika Ghats, the two cremation grounds,

smack bang in the middle of the huge crescent of ghats, in full public view.

This is something quite frankly that most people who have grown up in European

and American cultures have simply never seen., where death is carefully hidden

away in professional crematoriums and mortuaries. Indians, on the other hand,

make a very public display of death. They bring their newly dead, wrapped

in cloth, strung between bamboo litters carried through the crowded streets

to the edge of the water. A cremation pyre is built, the body bathed in Ganga

and then for several hours it will burn while relatives and priests chant

and perform the prescribed rituals. In Varanasi death is the essence of the

public life of the city. That is what makes it powerful. This is also what

makes it often incomprehensible to people seeing the city for the first time.

Same problem at Harishchandra and Manikarnika Ghats, the two cremation grounds,

smack bang in the middle of the huge crescent of ghats, in full public view.

This is something quite frankly that most people who have grown up in European

and American cultures have simply never seen., where death is carefully hidden

away in professional crematoriums and mortuaries. Indians, on the other hand,

make a very public display of death. They bring their newly dead, wrapped

in cloth, strung between bamboo litters carried through the crowded streets

to the edge of the water. A cremation pyre is built, the body bathed in Ganga

and then for several hours it will burn while relatives and priests chant

and perform the prescribed rituals. In Varanasi death is the essence of the

public life of the city. That is what makes it powerful. This is also what

makes it often incomprehensible to people seeing the city for the first time.

The first couple have come to seek his blessing for their nitya pooja - the

daily bathing ritual. They hand him fresh fruit and a few coins. Tripathi

begins the mantra. It starts off listing time and place in descending order

- Cosmos, India, Varanasi, Asi Ghat, month, day, name of the family - then

purpose (take a daily bath in Ganga). Next, an appeal to Mother Ganga, then

one to Vishnu to help one get through the day. The devotees give a symbolic

offering of fruit as proof of their good faith and Tripathi in return takes

tulsi leaves, while they touch Tripathi’s feet. This is the proof that

they have performed the initiation rite

The first couple have come to seek his blessing for their nitya pooja - the

daily bathing ritual. They hand him fresh fruit and a few coins. Tripathi

begins the mantra. It starts off listing time and place in descending order

- Cosmos, India, Varanasi, Asi Ghat, month, day, name of the family - then

purpose (take a daily bath in Ganga). Next, an appeal to Mother Ganga, then

one to Vishnu to help one get through the day. The devotees give a symbolic

offering of fruit as proof of their good faith and Tripathi in return takes

tulsi leaves, while they touch Tripathi’s feet. This is the proof that

they have performed the initiation rite . Tripathi blesses them: ‘With

the blessings of God you may now perform the rite.’

. Tripathi blesses them: ‘With

the blessings of God you may now perform the rite.’ the boat, Renuka ties a garland of flowers to the prow of the

boat. ‘This is the

the boat, Renuka ties a garland of flowers to the prow of the

boat. ‘This is the

cremated here.

cremated here. n any other water mass.’

n any other water mass.’