REPORTER'S NOTEBOOK

It’s late April. The

snows have finally melted and we set out from the town of Uttarkashi headed

deep into Ram Bhoomi - the Abode of the Gods.

Tomorrow is Ganga Dussehra, a joyous occasion for all, when Ganga is officially

re-installed in her summer temple at Gangotri, where according to legend she

was brought down to earth in the coils of Lord Shiva’s hair.

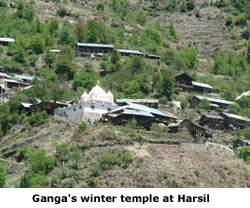

First stop is the tiny village of Bhaironghati, where the goddess will stay

overnight. She was fetched by a party this morning from her winter temple

lower down in the valley.

Brahmin cooks are preparing

the langar to feed the devotees who are accompanying the goddess on her journey

- huge metal cooking pots are being scraped clean, ready for chawal (rice)

and dal (lentils). Most Garhwalis are strictly vegetarian, abstaining even

from eggs.

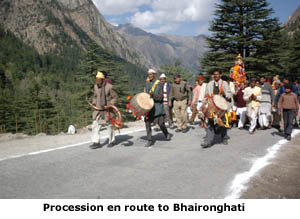

From far below I can hear a very distant rhythmical

thud — drums. How far away? Impossible to say. Sounds carry over such

huge distances, even in the plains. There is nothing to do but sit and wait.

It begins to rain and I seek shelter inside Lord Bhairav’s temple. A

group of donkeys waiting patiently outside the shrine get restless and move

off to investigate or seek shelter under the trees, bells tinkling brightly

in the mountain air. The sound of the distant cortege fades in and out, like

the signal of a mobile phone, as the goddess negotiates the many hairpins.

The thud of the dhol is louder, nearer, now punctuated by the occasional bleat

of a mountain horn and shouts of ‘Ganga ki jay.’

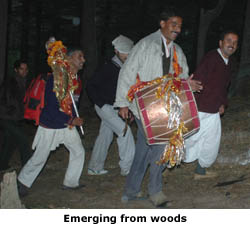

And then, she is upon us all at once, taking

a shortcut through the pines. Two drummers emerge: a man playing a two-sided

dhol and a kid traipsing along with a small, tambourine-like drum called a

damaum. They’re followed by a massive, curled, serpent-like hunting

horn. This ran singhar is very old, patched in gold, and carried by an equally

venerable man wearing huge spectacles with mismatched glass pieces, a patched

Harris tweed jacket and dhoti. Right behind them is the goddess Ganga, no

more than three feet high, swathed in red and gold cloth and borne forth on

her palanquin, on the shoulders of four young men. Straggling behind are an

assortment of devotees, the occasional policeman and a handful of families,

small children riding on their father’s shoulders.

And then, she is upon us all at once, taking

a shortcut through the pines. Two drummers emerge: a man playing a two-sided

dhol and a kid traipsing along with a small, tambourine-like drum called a

damaum. They’re followed by a massive, curled, serpent-like hunting

horn. This ran singhar is very old, patched in gold, and carried by an equally

venerable man wearing huge spectacles with mismatched glass pieces, a patched

Harris tweed jacket and dhoti. Right behind them is the goddess Ganga, no

more than three feet high, swathed in red and gold cloth and borne forth on

her palanquin, on the shoulders of four young men. Straggling behind are an

assortment of devotees, the occasional policeman and a handful of families,

small children riding on their father’s shoulders.

Ganga is carried up the steps

into the sanctum sanctorum, already occupied by Lord Bhairav. Thirty minutes

of mantras, bhajans and then a full-throated recitation of the fifty-two slokas

of the full ‘Ganga Lahiri’ (‘The Waves of the Ganga’),

a poem written by the seventeenth-century Sanskrit poet and scholar Jagannathan

in Varanasi.

Jagannathan was a South Indian Brahmin who is

said to have contracted leprosy as a result of a liaison with a married Muslim

woman. (Popular Indian belief views leprosy as the physical evidence of moral

corruption.) So Jagannathan came to Varanasi to be cured of his leprosy by

the waters of Ganga. Legend claims that each verse corresponds to the waters

of Ganga, rising a step at a time up Panchganga Ghat until the water reached

the final step and Jagannathan and his Muslim lover drowned.

The river is very much a goddess here. Ashok

Semwal, the President of the temple committee, says, ‘Narayan means

God. Nar is our word for water and water forms the base of our life. So water

equals God.’ Mr Semwal admits the river is highly polluted down in the

plains. ‘But not here in the Himalayas! Ganga is not like other rivers,

like the Yamuna or the Satluj. It can kill germs within ten minutes because

it has unique self-purifying powers.’

I ask him: ‘Is it true that if I drink

Ganga jal at Gaumukh I’ll live a hundred years but if I drink it at

Gangotri I’ll only live for ten years?’ Roars of laughter answer

me. But he confirms the rumour. ‘Yes, it’s true that if you drink

the Ganga jal at Gaumukh you’ll live a hundred years.

Next morning, even though we’re up early

Ganga’s beaten us to it: she already left at six o’clock for her

final climb to Gangotri. Today also marks the official reopening of the town

from winter hibernation. Telephones will start working again, much to my assistant

Aditi’s relief - she’s desperate to call home to her mother in

Mumbai.

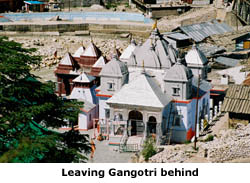

The temple itself is curiously small. The present

one was built in 1800 by a Sikh general, Amar Thapar Singh, and is said to

be constructed on top of a stone where King Bhagirath performed his tapasya,

standing on one leg for a thousand years. Whatever, it worked! It’s

a very small, squat building built of blocks of granite with a roof of tin

(the guidebooks say metal). In front of it is a courtyard paved with slate

flagstones and encircled by a wall set into the hillside. The other side leads

down to the river, which is churning happily down its rocky bed.

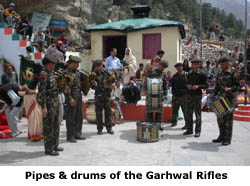

I can now hear the distant

thud of the drums. The procession is on its way down the long bazaar. It enters

through an archway from the bazaar, led by bagpipers from the Garhwal Rifles.

Behind them is the palanquin, in which rides the deity, freshly adorned with

marigolds, irises, roses and red silk. In statues and paintings Ganga is usually

depicted as a very feminine goddess in earthly form. But the goddess who’s

being reinstated today doesn’t look like that goddess at all. Underneath

her silks she’s a highly abstract modern sculpture, a silver rectangle

on end with an attached chimney, the whole ensemble no more than three feet

tall. The ornate burgundy-red skirts offer the only clue to her gender. Unless,

of course, this is merely her traveling case, while the real goddess is snugly

cocooned inside, totally hidden from human gaze.

while the real goddess is snugly

cocooned inside, totally hidden from human gaze.

She’s followed by the faithful from Harsil

who brought her up to Bhaironghati the previous evening, the two drummers,

the venerable ran singhar and its equally ancient performer, now supplemented

by several other drums. The good, the great, and everyone else, with sadhus

bundled up in warm clothes, bring up the rear. They march round behind the

temple to the main gates. The pipes move off to the edge of the courtyard,

the dhol, damaum and ran singhar a safe distance away so each can play to

a different section of the crowd - which by now is quite large - while the

deity is solemnly carried through the iron gates, up steps and into the sanctum

sanctorum of the temple. Anyone with any sort of camera is trying to climb

the wrought-iron bars and get a shot of the goddess. Two queues form - VIPs

to the left, others to the right. VIPs get to go in first for darshan. It

will take at least an hour. The sun is warm, the crowd good-natured; the right

day for a holy occasion.

The four pipers and a big

bass drum launch into a spirited medley of Garhwal Highland marching songs.

Over a crackling PA system the priests are chanting their slokas inside while

the crowd waits, trays of offerings held in anticipation. To one side a group

of villagers - mostly women, it appears - are sitting on the flagstones chatting

round a small deity called Bhauknath, who’s seated in a silver carriage

set into a long palanquin covered with blood-red cloth. Their village is Kaufnal,

near Uttarkashi, and they’ve brought their goddess just to see Ganga.

They bathed her at four o’clock this morning and this afternoon they’ll

head back home. The village poojari Kamal Singh starts retelling the whole

story of King Sagar and Bhagirath. Meanwhile, people are lining up to receive

darshan inside the temple. One woman, Runu De from Chandannagar, just north

of Kolkata, has brought her two daughters. She says, ‘The Ganga flows

in front of my house. It’s so much a part of my everyday life. We bathe

in her, we cross her every day in a launch. So we had to come and see where

it all starts.’

I mingle with the crowds, waiting to get darshan.

I spot the old man who’s been playing the ran singhar serpent horn.

His name is Mangaldas and he’s been playing the instrument since he

was twelve years old when it must have been bigger than him. He says he’s

now over eighty. Next to him stands a sadhu called Krishna Anand from Vrindavan.

He regularly makes the char dham yatra.

‘Why do you come here?’ I ask him.

His reply will sound very profound on radio, later: ‘Someone calls me

here. In the summer I go up to Gaumukh and Tapoban.’ Ten minutes later

we run into Krishna Anand again. This time he wants me to give him five hundred

rupees to buy a shawl to keep himself warm. I decline with a clear conscience

- I only have forty rupees in my kurta.

While I’ve been talking to Mangaldas and

Krishna Anand, Aditi and I lose contact with Nidish and the others, temporarily.

In search of him, Aditi and I wander down to the river to shallow concrete

bathing ghats where a handful of hardy souls are bathing in the fast-flowing

water that can’t be much above freezing point. Beside them stands a

large bell hanging from a wooden frame. Back home I have a print of a famous

lithograph by the nineteenth-century British painter William Simpson of this

exact same scene — pilgrims getting dressed at the edge of the Bhagirathi,

a similar bell in the foreground. The river is a fierce and shallow mountain

stream pouring down over boulders, not something anyone can really stand up

in away from the shore. I know: I tried to ford it and was swept over. (In

the plains Ganga is also shallow, but muddy and slow-moving.)

To his credit Simpson’s

lithograph shows the river as it is, not a broad Himalayan Thames as others

depict it. These colonial paintings and drawings are interesting in their

approach because, like the Hudson River Valley School in Upper New York state,

they often recast landscapes into familiar landscapes European viewers could

relate to. Many of Simpson’s contemporaries depict the valleys here

as gentle but gloomy cousins of a Scottish glen. They downplay the altitude

(after all, we’re at more than ten thousand feet here), in favour of

recreating the feel of the rolling hills of the Scottish Highlands (between

one and three thousand feet maximum). Not Simpson.

Should I undress and take a dip or find out

first how cold it really is? I choose my victim with care - Sriram Thappar

- a middle-aged man just coming out of the water and not shivering noticeably.

‘How cold is the water?’ ‘Minus two celsius,’ he replies.

Forget it! Sriram Thappar comes from Mumbai, and is up here with five other

families. This afternoon they’ll head back by car to Uttarkashi, then

by bus from Haridwar to Delhi, and by overnight train back to Mumbai.

‘Why do you come and bathe in this water,

when it’s so cold?’ I ask.

“Because I believe in Ganga. I believe

Ganga is God. I have a bath because it is our tradition. Here if you have

a bath you are purified. I believe this river is another form of God.’

Has Gangotri lived up to his expectations? ‘I

had this desire in my heart to come and worship here. That has been fulfilled.’

Another man from the same party - Harish Kumar - is busy filling plastic bottles

with Ganga jal. Harish Kumar has come for a very specific medical purpose.

He has Type 1 Diabetes. He swears Ganga jal lowers blood sugar: ‘I’ve

been staying in Haridwar for the past fifteen days, taking Ganga jal regularly.

My diabetes is hereditary and I know what it can do later on; my father died

when he was just fifty-five. Normally my blood sugar after meals is one eighty,

which is high. Here it’s down to one thirty.’

We cross back over a wooden

bridge to another Garhwal Mandal Vikas Nigam resthouse; our booking here got

bumped off the list so some VIPs could rest before today’s ceremony.

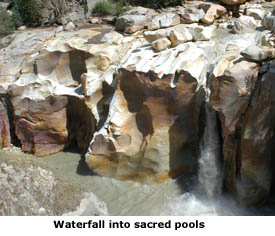

From the bridge I gaze down at the extraordinary series of pale granite cataracts

that have been carved into surrealist shapes by the sheer force of the river.

Both in colour and texture they look like whipped meringue, even though they’re

as hard as bone, official Gangotri leucogranite. Below them are three pools

- Brahmkund, Gaurikund, Vishnukund. Ganga is said to have descended at this

precise spot. These pools are therefore the most sacred places to bathe, though

how you get down to them is a mystery. When the water’s clear, you can

see submerged lingams, reminding me that Shiva must indeed have been here.

We cross back over a wooden

bridge to another Garhwal Mandal Vikas Nigam resthouse; our booking here got

bumped off the list so some VIPs could rest before today’s ceremony.

From the bridge I gaze down at the extraordinary series of pale granite cataracts

that have been carved into surrealist shapes by the sheer force of the river.

Both in colour and texture they look like whipped meringue, even though they’re

as hard as bone, official Gangotri leucogranite. Below them are three pools

- Brahmkund, Gaurikund, Vishnukund. Ganga is said to have descended at this

precise spot. These pools are therefore the most sacred places to bathe, though

how you get down to them is a mystery. When the water’s clear, you can

see submerged lingams, reminding me that Shiva must indeed have been here.

That evening, when it’s dark, Aditi and

I return to the temple. There are only a handful of people about. The evening

aarti is unusual - five different bells rung in sequence like English church

bells, the ubiquitous thud of the dhol and the plaintive call of the ran singhar.

While the priest is chanting slokas, something unusual (and very auspicious

according to Aditi) occurs. A grey dove flies out of the sanctum sanctorum,

takes a turn around the temple and then returns inside. A perfect end to a

very special day.

If mythologically these three

pools are the source of Ganga, where is the actual physical source? The river

emerges from under a glacier at Gaumukh but it’s already fully formed

- more than a foot deep and thirty feet wide. Scarcely a spring. So does it

make sense to continue to refer to Gaumukh as the source? Does it come from

somewhere further away under the Gangotri glacier? Nearer Badrinath? Could

the ancients conceivably have been right all along? This would mean that it

actually comes from the slopes of Mount Kailash and Lake Mansarovar (over

the border in Tibet) and flows underground through the drainage divide of

the High Himalayas, in defiance of all-known laws of modern science.

If mythologically these three

pools are the source of Ganga, where is the actual physical source? The river

emerges from under a glacier at Gaumukh but it’s already fully formed

- more than a foot deep and thirty feet wide. Scarcely a spring. So does it

make sense to continue to refer to Gaumukh as the source? Does it come from

somewhere further away under the Gangotri glacier? Nearer Badrinath? Could

the ancients conceivably have been right all along? This would mean that it

actually comes from the slopes of Mount Kailash and Lake Mansarovar (over

the border in Tibet) and flows underground through the drainage divide of

the High Himalayas, in defiance of all-known laws of modern science.

Can anyone ever really pinpoint the original

spot, the original drop of liquid? The bigger question: is it ultimately that

important?

The question was important to Europeans of very

early times. Prior to the sixteenth century, European geographers such as

Ptolemy and early Italian and Dutch cartographers tried to indicate the source

of the river on their maps. Jesuit missionaries somehow travelled to Lake

Mansarovar in the early seventeenth century and brought back the legend that

this was the source of Ganga. Chinese cartographers were sent to Tibet and

came back with much the same story, and it received an official stamp of approval

when this was published in 1733 as part of the four-volume Description de

l’Empire de la Chine, and later in James Rennel’s Memoir of a

Map of Hindoostan in 1783. But this was pretty tenuous scholarship at best.

So the East India Company sent Captain Webb

in 1808 to ‘survey the Ganges from Hurdwar to Gungoutri (or the Cow’s

Mouth), where that River is stated by Major Rennell to force its way through

the Himalaia Mountains by a Subterraneous passage but it is said by some natives

who have visited the spot to fall from an eminence in the form of a cascade.’

The expedition never made it as far as Gangotri. But they did gather reliable

information that ‘the Source of the River is more remote than the place

called Gung outri, which is merely the point where it issues from the Himalaia,

not as is related, through a Secret passage or Cavern bearing any similitude

to a cow’s mouth...although the access be so obstructed as to exclude

all further research.’

James Baillie Fraser was the first European

to actually reach Gangotri in 1815, followed two years later by Captain JA

Hodgson, who continued up to Gaumukh and officially discovered the source

of Ganga. Tomorrow, we will make that same journey.

But in reality we walk straight into a blizzard,

so have to make camp at Chirbasa - the place of the pines. We all go to bed

that night fully-clothed, taking refuge inside extreme weather sleeping bags

and the wet snow crushes the sides of the tent, increasing our sense of claustrophobia.

But what’s the alternative - to go out? Not until the snowfall has ceased.

Next morning, the sky is clear.

The mountain sides appear to be dusted with a light coating of icing sugar,

their peaks gleaming pale gold in the morning sun. Outside a group of young

students, dressed just in track suits and sneakers, are playing volleyball.

Well-prepared, unlike us who have one book and a bottle of rum between us,

as well as several digital cameras. But you can’t eat cameras.

The Expedition to Gaumukh

Nidish decides to play it safe; we’ll stay here at Chirbasa, dry our clothes and get rested to make an all-out assault on Gaumukh the next day - there and back between sunrise and sundown. This sounds fine but the weather at this time of year is so unpredictable. Nidish and I take the opportunity to discuss what it means for him to be a Hindu.

Next morning we set out in

full hiker’s gear. The trek starts well enough, the trail level and

covered with pine needles for the first kilometre. Then it gets rougher; progress

slows as we advance from stone to stone. Donkeys trip past us on the way up,

with cases of soft drinks in panniers on either side.

Next morning we set out in

full hiker’s gear. The trek starts well enough, the trail level and

covered with pine needles for the first kilometre. Then it gets rougher; progress

slows as we advance from stone to stone. Donkeys trip past us on the way up,

with cases of soft drinks in panniers on either side.

Once, we come to what appears to be a simple

mountain stream. You can either cross it on a narrow wooden tree trunk or

take your chances skipping from rock to rock. I choose the latter method and

am across in no time. Most of the others opt for the tree trunk and have to

be guided across by a porter, or risk a fall into the icy stream and subsequent

paralysis. It takes half an hour for all of us to get across this otherwise

insignificant stream. Twice more we have to edge forward on hands and knees,

trekking poles extended towards helping hands because of rock slides. Lose

your balance and you can fall a thousand feet down into the valley.

Beyond Bhojbasa, which indeed is totally denuded

of all vegetation and would make a marvellous soccer or even cricket pitch

, the path deteriorates yet again. We walk past what must have been the tree

farm. A few stunted saplings are all that remain of the experiment. But there’s

a big metal sign:

A REQUEST

It is a religious ritual to collect the holy

water of the river Ganga from its proverbial source, Gaumukh. But to conserve

the flora, fauna, water and soil and not to litter around Gaumukh area is

not merely the religious ritual but true religiousness. Hence you should go

beyond the religious ritual and be truly religious. Don’t ever forget:

God and nature are synonymous with each other. Revering nature i s revering

God.

s revering

God.

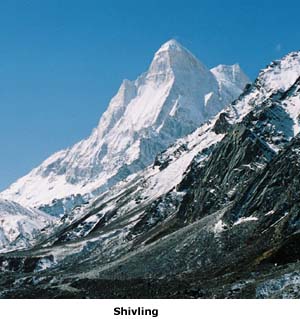

The mountains are indeed magnificent, worthy

of all their clichés, peaks covered in snow, framed by deep blue skies,

sun warming the entire valley. Ahead are the three Bhagirathi peaks, the other

side of the valley with huge landslides in the foreground, Shivling behind.

Every writer refers to its phallic shape, smooth,

round and aggressive. The base is indeed phallic, but its peak has been bent

back like the swing tip nose of the Concorde jetliner that can be adjusted

forward for takeoff, then straightened out for cruising at altitude. Anish

suddenly goes bounding up the scree beyond the path like some mountain goat.

For five minutes we watch and wait as he leaps and crouches from boulder to

rock, and then just as swiftly, he runs back down.

‘Did you see them?’ Complete blank.

‘See what?’

‘Himalayan tahr. Five of them. Look to the left of that bush.’

‘I don’t see anything.’ Anish

is getting impatient with me. But Martine knows what he’s talking about.

‘I can see them,’ she exclaims. ‘It’s incredible how

well they blend in with the rocks.’

Finally, a slight collective movement and these

mountain goats move five yards across the mo raine, perfectly camouflaged against

snow leopards and other predators.

raine, perfectly camouflaged against

snow leopards and other predators.

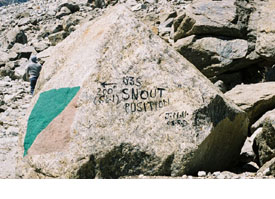

The going is rough and slow now. On a big boulder

on the side of the trail is written ‘1935 200’ SW SNOUT POSITION.’

We wonder, has the glacier really retreated that far in such a short time?

Nidish says he read in yesterday’s paper that it officially retreated

twenty-three metres last year. Geographers calculate it to have retreated

six hundred metres between 1935 and 1976. At this rate the Gangotri glacier

will have shrunk back all the way to Badrinath over thirty-five kilometres

due east, unless the warming trend turns out not to be irreversible global

warning, but merely cyclical warming and cooling.

We shed two layers of thermal

sweaters and Indian pilgrims regularly pass us in chappals and dhotis. Aditi

had been freezing when we set out; she’d packed only a light anorak

and sailing pants. Now she’s perfectly attired for the full midday sun

and skips along like the schoolgirls who must be up on the glacier, on their

way to Tapoban.

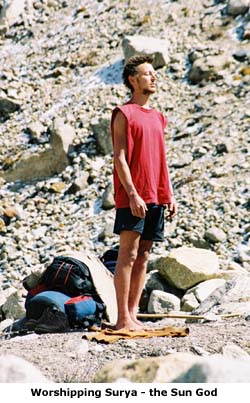

The rocks here have been set into a bed of cement,

so we have to stretch to move from rock to rock. This is a Himalayan Calvary,

I think. On Good Friday, Jesus Christ, wearing a crown of thorns, had to drag

both his body and a cross up a rocky path to Calvary, where he was to be crucified

later that day. I turn a corner on our path, and there he is - Jesus Christ!

Arms outstretched minus the cross, facing the sun. Must be a scarecrow. Martine

thinks it could be a statue. I move closer and details come into focus; curly

blond hair, closed eyes, blue running shorts, red sleeveless undershirt, backpack

behind, yellow towel laid out on the ground, plastic flip flops neatly to

one side. W hat we have here is a six-foot, thin as a rail Aryan from my part

of the world worshipping the Vedic sun god Surya in the abode

hat we have here is a six-foot, thin as a rail Aryan from my part

of the world worshipping the Vedic sun god Surya in the abode of the gods!

of the gods!

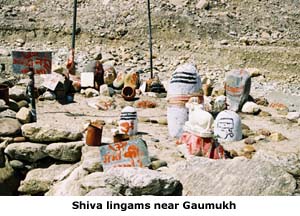

Next, I pass what looks like

a stone graveyard of various shaped stones decorated in paint and cloth. They

are Shiva lingams. Beside them sits a bearded Indian in orange turban and

dhoti, wearing what appears to be a pair of Ray-Ban sunglasses and sunning

himself. He gives us a Vietnam era sign of peace.

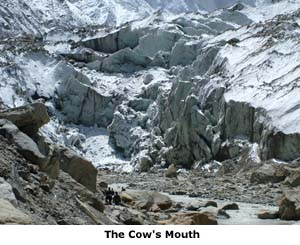

And then, there it is - Gaumukh. It’s

veined like a marbled cheese, tilting forward as if drunk, whole chunks ready

to collapse into the river bed - not at all as I’d imagined. No pure,

white, sheer wall, like an iceberg. But I’ve never seen a glacier before.

It looks old and tired from rough working snow, grinding and chewing rocks

up, spitting them out like some giant natural earthmover. Maybe this is how

they do strip mining in lands where man has little respect for the earth?

Captain J.A. Hodgson in 1815

may have been in awe, but he was also all business, a good surveyor. He describes:

‘A most wonderful scene. The Bhagirathi or Ganges issues from under

a very low arch at the foot of the grand snow bed.’ The river came from

under an arch in the face of the glacier, estimated by Hodgson to be three

hundred feet high. Nothing here resembles a cow’s mouth, there’s

just a glacier and a stream twenty-five feet wide and about fifteen inches

deep. I like Hodgson’s conclusion: ‘Believing this to be the first

appearance of the famous and true Ganges in day light, I saluted her with

a Bugle march.’

Captain J.A. Hodgson in 1815

may have been in awe, but he was also all business, a good surveyor. He describes:

‘A most wonderful scene. The Bhagirathi or Ganges issues from under

a very low arch at the foot of the grand snow bed.’ The river came from

under an arch in the face of the glacier, estimated by Hodgson to be three

hundred feet high. Nothing here resembles a cow’s mouth, there’s

just a glacier and a stream twenty-five feet wide and about fifteen inches

deep. I like Hodgson’s conclusion: ‘Believing this to be the first

appearance of the famous and true Ganges in day light, I saluted her with

a Bugle march.’

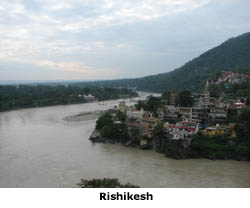

I take out my tape recorder and interview Babaji Samarth

Das instead. Samarth Das comes from Rishikesh. He’s been here before.

Barefoot, dressed only in dhoti and grey shawl, he’s come to collect

Ganga jal in a white glass jar that he’ll carry all the way down to

Rameswaram, the southernmost tip of India. There, he’ll do a pooja to

Bholenath, a form of Shiva, because he believes that if he takes Ganga jal

to Rameswaran and performs pooja there, boons will be granted to him.

‘I have no personal desires. My only desire

is that in every life that I will  be born I will be able to worship God and

be near him,’ he says.

be born I will be able to worship God and

be near him,’ he says.

Gaumukh is important for him because it is the

pure unadulterated Ganga - no mixing, no joining with other rivers. I wonder

if there are any other sacred rivers in India?

‘Yes there are, Narmada is Shiva’s

daughter.’ So what is Ganga?

Samarth Das retells the basic story of Shiva’s

locks and Bhagirath’s penance. He gets some of the details wrong but

the essentials right: she is the supreme river, pure and sacred. His faith

is simple and basic: ‘If you drink Ganga jal it purifies the soul in

spite of all the pollution.’

I wish him

godspeed. It’s well past midday and we have to get back to our camp

before nightfall. But before we leave I fill my water bottle with Ganga jal

and take a good swig to guarantee my hundred years. You never know! I gaze

up at the glacier, then back down the valley. The river runs down the valley:

after a quarter of a mile it just falls out of sight, drops off the earth,

leaving the valley and those snow-covered peaks. I remember learning to ski

down Alpine mountains where I would become terrified when the slope fell so

steeply I could no longer see the bottom. Yet here I have never felt afraid.

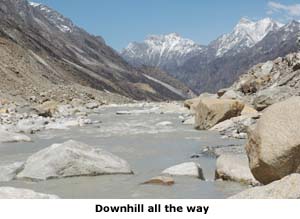

But it will be downhill hereon, and in more

ways than one. Ganga is her most pristine state here in Gaumukh. She is not

only a victim of global warming, but over the course of the next twenty-five

hundred kilometres she will also be raped, pillaged and de-sexed, until she

staggers exhausted into the Bay of Bengal at Sagar Island.

The problems start to appear

as soon as we start back down to Dehra Dun. Man always dumps waste into Ganga,

and to add to this, he interferes with the river, constantly diverting her

waters to generate electricity. Less than one hundred kilometres south, just

north of Uttarkashi, the river has been dammed up and diverted through pipes

to feed turbines to generate electricity. Below the dam the river bed is bone-dry

for several kilometres until the water is allowed back, just near the town.

Downstream from the town a cement factory pours slurry into the river. These

are not isolated instances; the demand for hydroelectricity is just too pressing.

The problems start to appear

as soon as we start back down to Dehra Dun. Man always dumps waste into Ganga,

and to add to this, he interferes with the river, constantly diverting her

waters to generate electricity. Less than one hundred kilometres south, just

north of Uttarkashi, the river has been dammed up and diverted through pipes

to feed turbines to generate electricity. Below the dam the river bed is bone-dry

for several kilometres until the water is allowed back, just near the town.

Downstream from the town a cement factory pours slurry into the river. These

are not isolated instances; the demand for hydroelectricity is just too pressing.

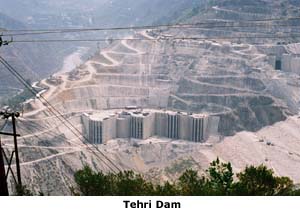

The mother and father of all dams is being built

at Tehri, just below the junction of the Bhilang river and the Bhagirathi.

Nehru would have called the Tehri dam a ‘temple of the future.’

The author Stephen Alter calls it ‘a form of sacrilege, obstructing

the inexorable current of a holy river that symbolizes the cosmos.’

The mother and father of all dams is being built

at Tehri, just below the junction of the Bhilang river and the Bhagirathi.

Nehru would have called the Tehri dam a ‘temple of the future.’

The author Stephen Alter calls it ‘a form of sacrilege, obstructing

the inexorable current of a holy river that symbolizes the cosmos.’

An entire valley is now being flooded by a huge,

earthen dam to generate electricity for Delhi (six hundred kilometres to the

south) and the state of Uttar Pradesh (population one hundred and eighty million

and rising). The lake will stretch back thirty-five kilometres, be five kilometres

wide. It will drown whole villages and productive farmland. Much of Bhagirathi–Bhilang

will be diverted through three giant turbines set into the mountainside, then

carried through a tunnel in the mountain and spat out again lower down.

Worse still, Tehri is in a major earthquake

zone - it sits on the same fault line as the site of the 2005 Kashmir earthquake.

But the Indian government stubbornly ignores environmental warnings because

this project is already forty-plus years in the making and has built up such

bureaucratic momentum that they are not about to abandon it now.

Nidish takes us to a spot

high above the actual dam. Down below thousands of construction workers -

ant-like figures - are scurrying to top off the dam. Stephen Alter compares

them to King Sagar’s sixty-thousand sons. A different historical analogy

springs to my mind: it’s like watching a diorama of the building of

the Egyptian pyramids in a science museum: scores, hundreds of dump trucks

move ant-like up a series of zigzag ramps cut into the dam face, carrying

their precious loads to the summit of this twenty-first century pyramid, just

as the slaves somehow pushed hundreds of thousands of giant stone cubes up

to the summit of the pharaonic mausoleums.

Nidish takes us to a spot

high above the actual dam. Down below thousands of construction workers -

ant-like figures - are scurrying to top off the dam. Stephen Alter compares

them to King Sagar’s sixty-thousand sons. A different historical analogy

springs to my mind: it’s like watching a diorama of the building of

the Egyptian pyramids in a science museum: scores, hundreds of dump trucks

move ant-like up a series of zigzag ramps cut into the dam face, carrying

their precious loads to the summit of this twenty-first century pyramid, just

as the slaves somehow pushed hundreds of thousands of giant stone cubes up

to the summit of the pharaonic mausoleums.

Another observation that intrigues me is that

I’ve yet to see anyone fishing in Ganga. I’m used to West Bengal

where fishing is in the air one breathes. Nidish says people in Garhwal are

not fish-eaters. And even if you wanted to fish they won’t give you

a permit. The Forestry Department classifies fish as wildlife, and wildlife

has to be preserved.

I ask Nidish whether the Ganga jal I drink lower

down will have the same magical properties as Gaumukh and Gangotri’s

waters.

‘I don’t know,’ he replies.

‘But as a Hindu I would say that after this dam starts functioning I

think the real Ganga will only be found down to Uttarkashi.’

So that does mean the Ganga below somehow won’t

be the real Ganga? Nidish yo-yos all over the place. In the same sentence

he can wear two different hats; as a respected environmentalist (he’s

a member of the government’s Advisory Panel on Ecology and Tourism),

and then back to his old line as a devout Hindu whose faith trumps his knowledge

of Himalayan ecology.

‘I’m not a scientist, but this is

what I believe. At Varanasi the water is already like a sewer and people are

drinking it and bathing in it, and they are alive and well. So the faith will

always be there, but I don’t think the water will have the same properties.’

‘I’m not a scientist, but this is

what I believe. At Varanasi the water is already like a sewer and people are

drinking it and bathing in it, and they are alive and well. So the faith will

always be there, but I don’t think the water will have the same properties.’

Nidish says he’s never been in favour

of this dam. He’s lived through the earthquake in 1991 that levelled

Uttarkashi. It measured 7.8 on the Richter scale and killed three thousand

people. As he reminds me: ‘Uttarkashi from Tehri is just about one and

a half hours drive.’ Anyway, what will happen to the silt that will

build up behind the dam? No one seems to have taken that into account. And

if the dam does break, Rishikesh, Haridwar, even Bijnor a hundred kilometres

south of Haridwar (site of yet another dam) will be washed away.

Nidish’s solution would be to encourage

the building of small check dams and local energy generation through micro-turbines.

‘In Switzerland I have seen small turbines that can generate electricity

for fifty, a hundred houses, a small village, and it doesn’t cost much.

Just two people to look after the turbine. Whereas here you have tho usands

of people working. And for what? This is not safe for this size project.’

usands

of people working. And for what? This is not safe for this size project.’

He says this alternative is already being used

here in Garhwal. ‘There’s a place in Garhwal we call the Valley

of Flowers. There’s a lot of water there, there’s a river, and

the Government of India has done a wonderful job. They installed small turbines

and they generated electricity. Now I admit the people who maintain the turbines

are not engineers and so when the turbines break down there’s no one

to fix them, but the idea is good.’

Small is indeed still beautiful. But engineers

usually prefer the grandeur and glory, the politicians and contractors moolah

- lots of it! Where’s the profit in sustainable development? This is

something that really gets Nidish going.

‘Tehri Dam is going to be a disaster for

the country in the coming years. To run a hydroelectricity project you need

water, not sand. One day that whole lake will be full of silt. And then where

the hell is my government is going to throw all that sand? Tehri is going

to become a white elephant. Concrete jungles are not balanced ecology.’